O estranho familiar Paula Siebra

Paula Siebra and the Strangely Familiar

It’s a vision of the everyday – strikingly ordinary, yet subtly unsettled by a hint of strangeness, as if the whole scene could suddenly tip into the realm of nightmares. A still life with a revolver, a pair of gloves and a rose, planted on a table. The composition of one of Paula Siebra’s first works for the exhibition seems straight out of an Agatha Christie novel. For the artist, detective fiction is a metaphor for painting. Not so much in the unravelling of the plot, but in the pleasure we take circling around it, like a bloodhound around its prey, tracing the contours of each character, deciphering their gestures, mapping the world they inhabit. There’s something magical in this kind of investigation, a process that crystallizes through intuition, often beyond the reach of language. Much like the challenge of putting a painting into words.

Paula Siebra is from Fortaleza, in the state of Ceara in northern Brazil. It’s where she grew up. She says she started drawing early on and trained her eye not in a fine arts museum but by visiting the folk arts museum in Dragão do Mar with her mom every Sunday. She remembers almost as vividly the melancholic strains of choro, this traditional music played within her family. For a moment, she nearly chose music over art. But images pulled her back in, and she enrolled in a painting course at the University of Rio de Janeiro. The first shapes that left an impression on her were ceramics, laces, and embroideries from her home region as well as simple images of ex-votos. In the first art books she got her hands on, she encountered Frida Kahlo and Balthus.

Of course, the exhibition also owes its title to Freud and his concept of the uncanny – or, as per François Roustang’s translation, the strangely familiar (l’étrange familier)– that which feels close yet remains hidden. Take, for instance, this mask left on a dresser, with a drawer half-open overflowing with letters and a carafe resting on a tablecloth creased in a peculiar way. Its presence is like a trace of a carnival past inadvertently forgotten – an objective encounter worthy of André Breton. This fascination with the everyday, paired with an attraction to a kind of magical realism, also emanates from her mother’s sewing box – an orange pincushion, a measuring tape loosely coiled – or in the careful arrangement of a well-packed suitcase. Not as a metaphor but simply as a display of the quiet diligence involved in folding striped shirts, tucking away a pair of pliers, a hairbrush, a book, and a pair of shoes inside an old crocodile-skin suitcase found at a flea market. Inside the suitcase, there’s a novel by a writer from her home region, its cover adorned with a woodcut print. She chose it because the image recalls the vernacular techniques she feels closest to. And the dominos? It’s always good to have a set on hand when you’re travelling: It’s an easy way to make friends.

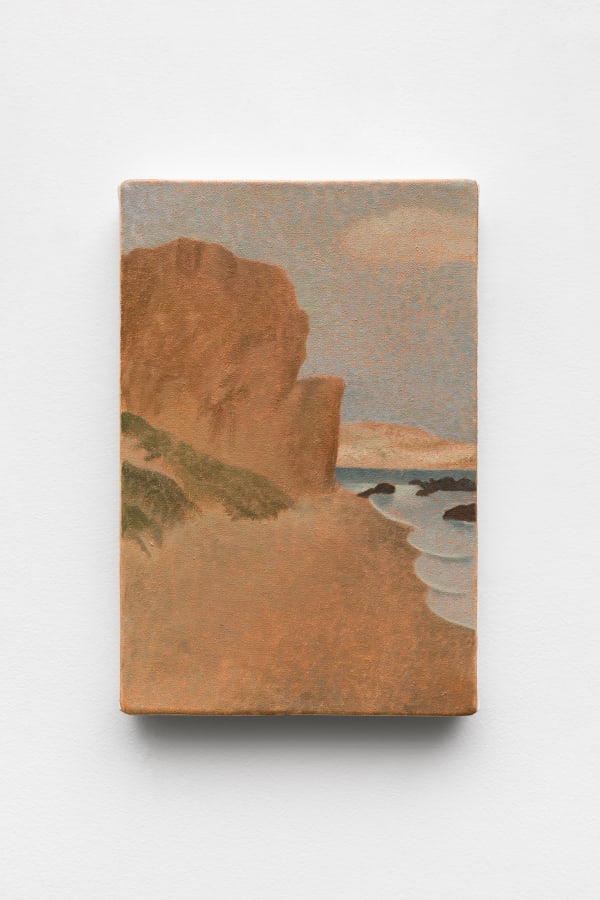

A series of landscapes accompany these scenes, like backdrops for narratives without a script. One must surrender to the quiet pleasure of this restrained painting. On the velvety petals of a plant, glistening beads of water evoke the morning dew. How does one paint dew? Paula Siebra wonders. Through atmosphere. Typically, her assistants prepare her canvases using local materials. She then primes them with an ochre or gray base, depending on the tonal range she aims to achieve. From there, she builds the image with countless layers of tiny, precise brushstrokes, using an almost dry paint. Her palettes tend to be homogenous. Though her brushwork is delicate, it accumulates in numerous layers to create a soft glow – like in the Venetian paintings she likes so much.

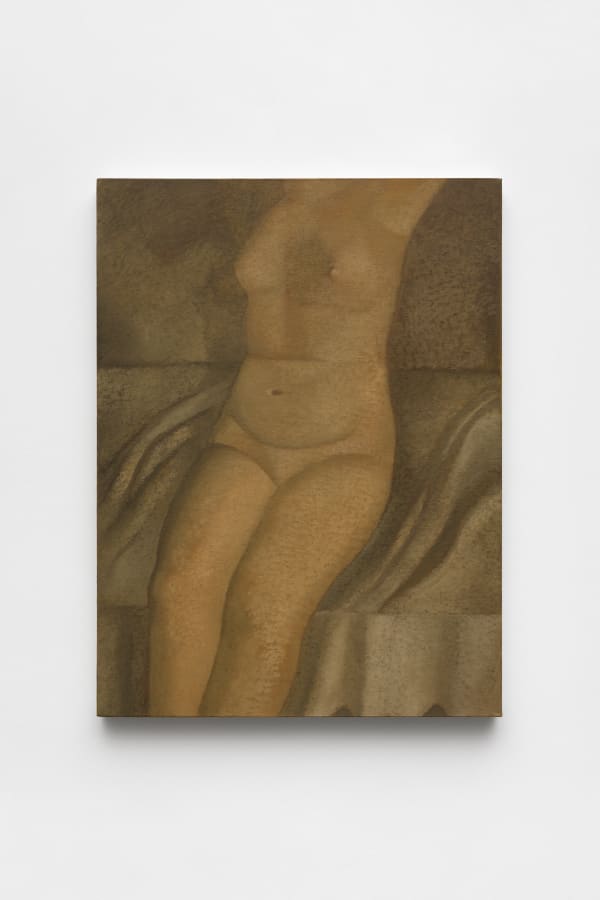

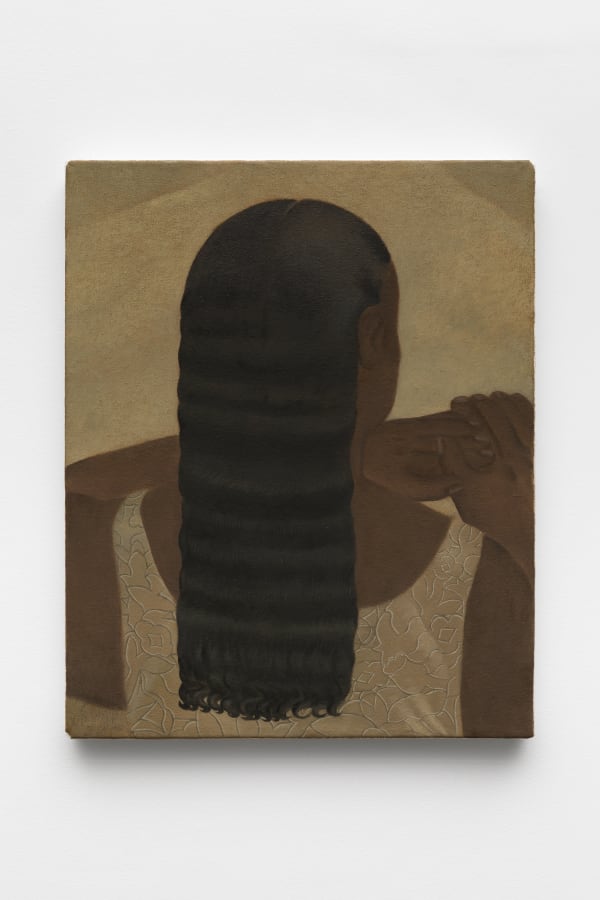

Her most enigmatic works are her figures – sometimes cropped, reduced to fragments, like ancient bas-reliefs. In fact, their skin often takes on the colour of stone. Paula Siebra draws inspiration from the Brazilian artist Vicente do Rego Monteiro (1889 – 1970) and the Italian painter Antonio Donghi (1897 – 1963), both of whom flirted with elements of naïve art. She studied Magritte’s paintings, particularly L’éternellement évident (1948) at MoMA, which left a deep impression on her. Domenico Gnoli features among her artistic heroes, a connection that becomes evident in her depictions of figures seen from the front or back, frozen in an embrace, or absorbed in meticulous activities – like examining the pearls of a necklace through a magnifying glass. Their hair is combed with deliberate precision, turned into abstract surfaces that resemble rivers or furrowed landscapes. They echo the same quiet obsessions that haunt her perfectly arranged suitcase – the pursuit of harmony.

– Anaël Pigeat