Artists include: Juan Pérez Agirregoikoa, Armando Andrade Tudela, Lucas Arruda, Karim Aïnouz, Adrián Balseca, Tosh Basco, Katinka Bock, Paloma Bosquê, Nina Canell, Guglielmo Castelli, Mariana Castillo Deball, Alejandro Cesarco, Henri Chopin, Marguerite Duras, Philipp Fleischmann, Sonia Gomes, Barbara Hammer, Runo Lagomarsino, Patricia Leite, Matthew Lutz-Kinoy, Paul Maheke, Hana Miletić, Charlotte Moth, Beatriz Santiago Muñoz, Paulo Nazareth, Lygia Pape, Yvonne Rainer, Letícia Ramos, Mauro Restiffe, Luiz Roque, Giangiacomo Rossetti, Maaike Schoorel, Jeremy Shaw, Paula Siebra, Willard Steiner & Ralph Van Dyke, Davide Stucchi, Kishio Suga, Pol Taburet, Sophie Thun and Erika Verzutti.

“Our hands empty except for our hands.” Ocean Vuong – On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous (2019)

“Hands are unbearably beautiful. They hold on to things. They let things go.” Mary Ruefle – The Cart, Selected Poems (2011)

I see no difference between a handshake and a poem, Paul Celan once wrote in a letter to Hans Bender. Almost four decades later, another poet, Claudia Rankine, beautifully unpacked Celan’s blunt statement in her book-length prose poem Don’t Let Me Be Lonely (2004):

“The handshake is our decided ritual of both asserting (I am here) and handing over (here) a self to another. Hence, the poem is that—Here. I am here. This conflation of the solidity of presence with the offering of this same presence perhaps has everything to do with being alive. […] Here you are. […] ‘Here’ both recognizes and demands recognition […] For something to be handed over, a hand must extend, and a hand must receive.”¹

Across cultures, since time immemorial, the hand has appeared as a philosophical subject and symbol,² from prehistoric caves to pre-Socratic philosophy, from French post-structuralism to Indian mudras. The ancient handprints found on cave walls worldwide were largely created by spitting pigment over a hand placed there, or stamping the hand against the stone wall to leave an imprint: it is here, if anywhere, that humans have made their lasting marks. The contrast between the ephemerality of the living body and the incommensurate time of the rock is the opening gambit of everything that much later – and still arguably – would come to be called culture. These ancient stencils seem to tell us that our distant ancestors once stood within huge hollow rocks under flickering light and saw a place to begin. Maybe they painted in silence or were performing some sort of ritual; most probably, women did it… we will never fully know. The only lasting certainty is that they left something behind in the darkness, something astonishingly beautiful and yet oblique. Beyond the fascinating genealogical clues and poetic potential caves might offer, the wounds our species have carved onto the land and into the geological strata must be acknowledged. Novelist and poet Anne Michaels reminds us of the carbon remains of previously living entities in non-living surfaces:

“The black pigment used to paint the animals at Lascaux was made of manganese dioxide and ground quartz; and almost half the mixture was calcium phosphate. Calcium phosphate is produced by heating bone four hundred degrees Celsius, then grinding it. We made our paints from the bones of the animals we painted. No image forgets this origin.”³

Indeed, no image forgets this origin. In her short film The Negative Hands, Marguerite Duras captured Paris in 1978. Through a car window, the camera scans the city during the early hours of the day. Amid a bottomless blue sky, grim music breaks in accompanied by the filmmaker’s low disembodied voice talking about the Magdalenian caves on the European Atlantic coast, where a profusion of handprints had been recently discovered – a sort of petrified cry, she says, stamped against the cave wall some 30,000 years ago.

The subjective, gliding camera continues the stroll until it incidentally captures a specific segment of society – those invisible actors who clean the streets, houses, and offices, soon to retreat as the city awakens for those arriving later in the working day. The images of the waking city and the voiceover are implicitly linked through an analogy between the ancient man in the grotto and those that work at dawn, who are predominantly immigrants, and non-whites.4 The anonymous handprints in the cave call to us as a gesture of appeal, directed to whoever can hear it – I will love anyone who hears me screaming, the narrator whispers.

At this point, we reach the exhibition’s underlying idea: the hand, what it touches and circumscribes, and what it lets slip away. The reunion of the artworks in space is also an invitation to think about tactile hands and their imprints as a pathway for a broader consideration of how subjects emerge as a constellation between inhuman time, nonhuman forces, and geologic materiality – a queer genealogy rather than an exceptional model of human subjectivity.5 So, let’s go back to the concave surface of the rock and reframe it not as the birthplace of a univocally authored and gendered identity – or the ground zero of human imprinting upon “nature” – but as a passageway into immeasurable geological time. The hand on the rock, the hand holding another hand, the hand that caresses, creates, and destroys as a reconsideration of the way we relate to living and non-living beings. This change in perspective opens a mode of sensitivity that seems fit for dealing with our dire present, starting from the simple acknowledgment that all things exist through mutual engagement.

We must also remember that touch is always relational, as it continuously changes the contours of the self, the other, and the world around us. But there always seems to be something missing, something unattainable. One can never fully touch anything, and, at the same time, there is no such thing as total isolation. Things are neither intact nor entirely in contact.6 Is touching something that we do? Or is it something that happens to us? Can one really touch without being touched? It makes us aware of our bodily existence: something is offered, but in that offer, something is taken away.

By occupying a house in Paris’ oldest planned square, the Place des Vosges, the works brought there for display or created specifically for that site mark the transformation of a former residential home and long-closed psychoanalytic clinic into a new contemporary art gallery. Like anonymous handprints in a cave, they leave imprints on a different time, touching someone else’s memories and listening to lingering voices to form an elliptical and allusive environment. Forms interrupt and complement each other ceaselessly, as if many hands were superimposed with a strange coherence that is not that of narrative. Duras’ poignant reflection on the prehistoric act of mark-making stands as the cornerstone of this collective construction. Decades later, screening the film in the city where she once lived and worked invites a similar gesture: to reach out to another time and add a new layer of presence to a place where so many have passed. As we see Paris captured by her lens, an inescapable question arises: will the French capital still exist in 30,000 years’ time? Will Place des Vosges’ rock-solid walls, standing since 1615, outlive our species? Again, we could never know.

Paul Celan saw poems as perpetually en route: they head toward something. Toward what? Toward something open, inhabitable – perhaps an approachable “you” or an approachable reality.7 To Celan, the poem (for us, the artwork) is a gift, an offering of one’s lived, embodied, historical singularity, accompanied by the contingent and fragile hope that someone’s truthful hands will receive it. In this sense, this exhibition is an attempt to grasp – or maybe to act out – what happens when an infinity of others – other beings, other spaces, other times – are invoked. Again, for something to be handed over, a hand must be extended, and a hand must be ready to receive it. As the poet Ocean Vuong writes, sometimes your hand is all you have to hold yourself to this world.8 Touching is reassuring, and so is art.

— Fernanda Brenner

1 Rankine, C. (2004). Don’t Let Me Be Lonely: An American Lyric. Minneapolis, Minnesota: Graywolf Press, pp. 130–1.

2 The idea of the hand as a primary instrument of human thinking begins with Anaxagoras and extends to Heidegger, Derrida, and Merleau- Ponty, who configured their philosophical agenda around its qualities.

3 Michaels, A. (2009). The Winter Vaults. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart.

4 Marguerite Duras interview in Mascolo, J. and Beaujour, J. (1984), La caverne noire.

5 Yusoff, K. (2015). Geologic subjects: nonhuman origins, geomorphic aesthetics and the art of becoming inhuman. Cultural Geographies, 22(3), 383–407.

6 Derrida, J. (2005). On Touching: Jean-Luc Nancy. Trans. Christine Irizarry. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press.

7 Celan,P (1958).Speech on the Occasion of Receiving the Literature Prize of the Free Hanseatic City of Bremen.

8 Vuong, O. (2017). Night Sky With Exit Wounds. London: Jonathan Cape.

-

Juan Perez Agirregoikoa, Lacan I love u, 2011

Juan Perez Agirregoikoa, Lacan I love u, 2011 -

Juan Perez Agirregoikoa, Needs re-education, 2011

Juan Perez Agirregoikoa, Needs re-education, 2011 -

Karim Aïnouz, Brighther Than The Sun / Plus éclatant que le soleil, 2023

Karim Aïnouz, Brighther Than The Sun / Plus éclatant que le soleil, 2023 -

Lucas Arruda, Untitled (from the Deserto-Modelo series), 2023

Lucas Arruda, Untitled (from the Deserto-Modelo series), 2023 -

Adrián Balseca, Glove (from the series “The Skin of Labour“), 2016

Adrián Balseca, Glove (from the series “The Skin of Labour“), 2016 -

Tosh Basco, Untitled Hand Dance, 2021

Tosh Basco, Untitled Hand Dance, 2021 -

Katinka Bock, Digital, 2023

Katinka Bock, Digital, 2023 -

Paloma Bosquê, Plate, 2023

Paloma Bosquê, Plate, 2023 -

Nina Canell, Free-Space Path Loss, 2017

Nina Canell, Free-Space Path Loss, 2017 -

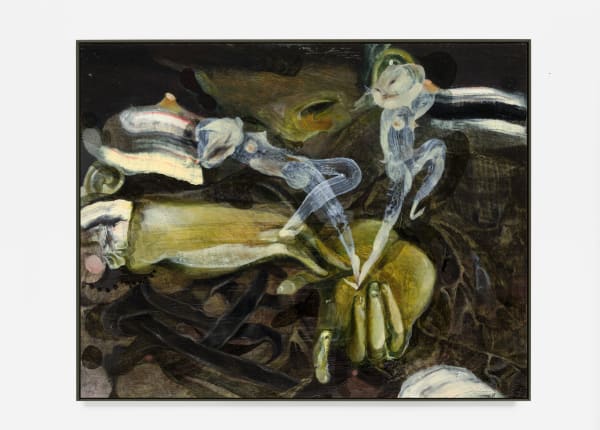

Guglielmo Castelli, Confusion Facts with Representation, 2023

Guglielmo Castelli, Confusion Facts with Representation, 2023 -

Alejandro Cesarco, The Dreams I’ve Left Behind, 2015

Alejandro Cesarco, The Dreams I’ve Left Behind, 2015 -

Henri Chopin, Jeu Graphique, 1983

Henri Chopin, Jeu Graphique, 1983 -

Henri Chopin, Mouvance de l’oeil, 1983

Henri Chopin, Mouvance de l’oeil, 1983 -

Mariana Castillo Deball, Toward and away like the hand, 2023

Mariana Castillo Deball, Toward and away like the hand, 2023 -

Mariana Castillo Deball, As they forage in secret on our idea of distortion, 2023

Mariana Castillo Deball, As they forage in secret on our idea of distortion, 2023 -

Marguerite Duras, Les Mains négatives, 1979

Marguerite Duras, Les Mains négatives, 1979 -

Philipp Fleischmann, Film sculpture (4), 2023

Philipp Fleischmann, Film sculpture (4), 2023 -

Sonia Gomes, Nebulosa 2, 2022

Sonia Gomes, Nebulosa 2, 2022 -

Barbara Hammer, Sync Touch, 1981

Barbara Hammer, Sync Touch, 1981 -

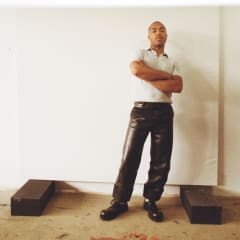

Runo Lagomarsino, America I use your name in vain, 2019

Runo Lagomarsino, America I use your name in vain, 2019 -

Patricia Leite, Untitled, 2023

Patricia Leite, Untitled, 2023 -

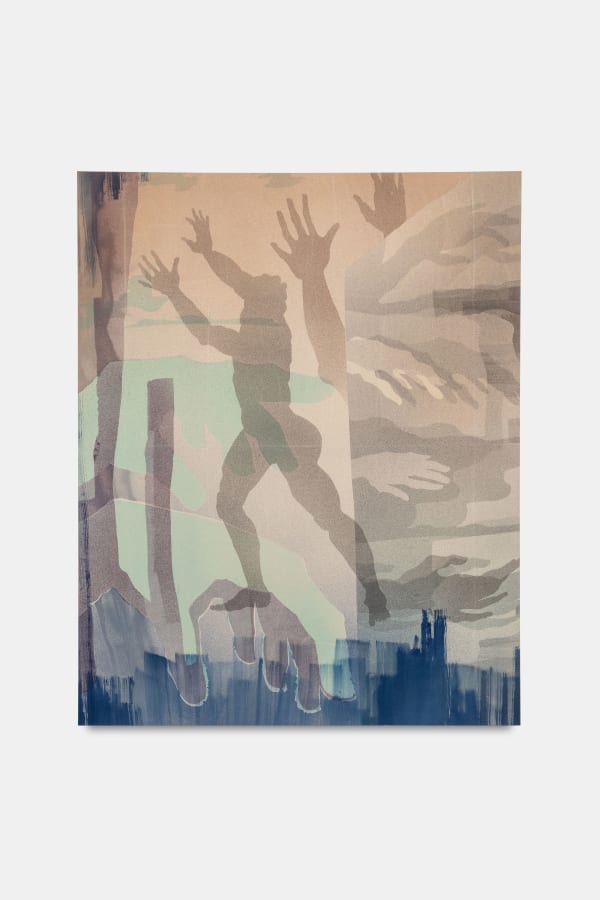

Matthew Lutz-Kinoy, Cave Simulation as luminescent event, 2023

Matthew Lutz-Kinoy, Cave Simulation as luminescent event, 2023 -

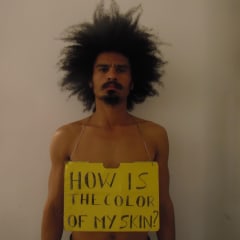

Paul Maheke, We took a sip from the devil's cup (4), 2020

Paul Maheke, We took a sip from the devil's cup (4), 2020 -

Hana Miletić, Materials, 2023

Hana Miletić, Materials, 2023 -

Charlotte Moth, On brilliant days, dark days, dawn, dusk and afternoons, by moonlight, 2023

Charlotte Moth, On brilliant days, dark days, dawn, dusk and afternoons, by moonlight, 2023 -

Beatriz Santiago Muñoz, CORTE DE MANOS, 2023

Beatriz Santiago Muñoz, CORTE DE MANOS, 2023 -

Paulo Nazareth, Chainsaw, 2022

Paulo Nazareth, Chainsaw, 2022 -

Paulo Nazareth, Rolleytruck, 2022

Paulo Nazareth, Rolleytruck, 2022 -

Paulo Nazareth, CA - Ita Gyra , 2018

Paulo Nazareth, CA - Ita Gyra , 2018 -

Paulo Nazareth, CA - Ita Gyra Guasu, 2018

Paulo Nazareth, CA - Ita Gyra Guasu, 2018 -

Lygia Pape, A Mão do Povo, 1975

Lygia Pape, A Mão do Povo, 1975 -

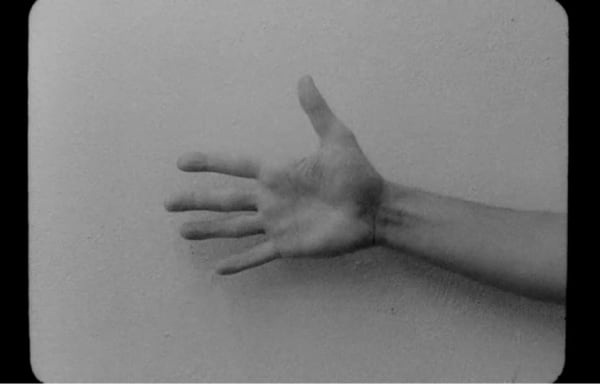

Yvonne Rainer, The Hand Movie, 1966

Yvonne Rainer, The Hand Movie, 1966 -

Leticia Ramos, Gráfico, 2017

Leticia Ramos, Gráfico, 2017 -

Leticia Ramos, Gráfico, 2017

Leticia Ramos, Gráfico, 2017 -

Leticia Ramos, Gráfico, 2017

Leticia Ramos, Gráfico, 2017 -

Mauro Restiffe, A maçã, 2020

Mauro Restiffe, A maçã, 2020 -

Mauro Restiffe, Luz, 2021

Mauro Restiffe, Luz, 2021 -

Mauro Restiffe, Projeto Piauí #8, 2015

Mauro Restiffe, Projeto Piauí #8, 2015 -

Mauro Restiffe, Rochelle, 2023

Mauro Restiffe, Rochelle, 2023 -

Mauro Restiffe, Brasa, 2019

Mauro Restiffe, Brasa, 2019 -

Mauro Restiffe, Brinde, 2020

Mauro Restiffe, Brinde, 2020 -

Mauro Restiffe, Pai se segurando, 2021

Mauro Restiffe, Pai se segurando, 2021 -

Mauro Restiffe, Mão e vasos, 2016

Mauro Restiffe, Mão e vasos, 2016 -

Mauro Restiffe, Silhueta, 2021

Mauro Restiffe, Silhueta, 2021 -

Mauro Restiffe, Fernanda e Paloma no Balcão, 2018

Mauro Restiffe, Fernanda e Paloma no Balcão, 2018 -

Mauro Restiffe, Amantes, 2022

Mauro Restiffe, Amantes, 2022 -

Mauro Restiffe, Lulalá, 2022

Mauro Restiffe, Lulalá, 2022 -

Mauro Restiffe, Hands on the ceiling, 2001

Mauro Restiffe, Hands on the ceiling, 2001 -

Mauro Restiffe, Matheus ao sol, 2020

Mauro Restiffe, Matheus ao sol, 2020 -

Mauro Restiffe, Triângulo, 2022

Mauro Restiffe, Triângulo, 2022 -

Mauro Restiffe, Russia(Hands #2), 1996

Mauro Restiffe, Russia(Hands #2), 1996 -

Mauro Restiffe, Russia(Hands), 1996

Mauro Restiffe, Russia(Hands), 1996 -

Mauro Restiffe, Charlie touching the light, 2019

Mauro Restiffe, Charlie touching the light, 2019 -

Mauro Restiffe, Autorretrato com dedo na lente, 1988

Mauro Restiffe, Autorretrato com dedo na lente, 1988 -

Mauro Restiffe, João Maria, 2018

Mauro Restiffe, João Maria, 2018 -

Mauro Restiffe, Ao fim da noite em Lisboa, 2022

Mauro Restiffe, Ao fim da noite em Lisboa, 2022 -

Mauro Restiffe, Ana, 2022

Mauro Restiffe, Ana, 2022 -

Mauro Restiffe, Projeto Piauí #9, 2015

Mauro Restiffe, Projeto Piauí #9, 2015 -

Mauro Restiffe, Valdirlei, 2021

Mauro Restiffe, Valdirlei, 2021 -

Mauro Restiffe, Amantes #2, 2022

Mauro Restiffe, Amantes #2, 2022 -

Mauro Restiffe, Repouso, 2022

Mauro Restiffe, Repouso, 2022 -

Mauro Restiffe, Pia and Felipe on the dance floor, 2014

Mauro Restiffe, Pia and Felipe on the dance floor, 2014 -

Mauro Restiffe, Pierre, 2022

Mauro Restiffe, Pierre, 2022 -

Mauro Restiffe, Mãos da mãe, 2021

Mauro Restiffe, Mãos da mãe, 2021 -

Mauro Restiffe, Pedro e Marina acendendo os cigarros, 2018

Mauro Restiffe, Pedro e Marina acendendo os cigarros, 2018 -

Mauro Restiffe, Antonello, 2019

Mauro Restiffe, Antonello, 2019 -

Mauro Restiffe, Balada, 2019

Mauro Restiffe, Balada, 2019 -

Mauro Restiffe, I love fishing, 2010

Mauro Restiffe, I love fishing, 2010 -

Giangiacomo Rossetti, Cake (to celebrate), 2023

Giangiacomo Rossetti, Cake (to celebrate), 2023 -

Maaike Schoorel, Studio still life (dark small, with pencil cleaner & glass), 2023

Maaike Schoorel, Studio still life (dark small, with pencil cleaner & glass), 2023 -

Jeremy Shaw, Towards Universal Pattern Recognition (3-D Nightclub. Royal Oak. 11/8/88), 2023

Jeremy Shaw, Towards Universal Pattern Recognition (3-D Nightclub. Royal Oak. 11/8/88), 2023 -

Jeremy Shaw, Cathartic Illustration (Amplified), 2023

Jeremy Shaw, Cathartic Illustration (Amplified), 2023 -

Jeremy Shaw, Towards Universal Pattern Recognition (Darla Minor ’signs’ a song. MAY 24 1987), 2023

Jeremy Shaw, Towards Universal Pattern Recognition (Darla Minor ’signs’ a song. MAY 24 1987), 2023 -

Paula Siebra, Mãos acendendo um cachimbo / Duas mãos / Mãos descascando laranja, 2023

Paula Siebra, Mãos acendendo um cachimbo / Duas mãos / Mãos descascando laranja, 2023 -

Wilard Van Dyke & Ralph Steiner, Hands, 1934

Wilard Van Dyke & Ralph Steiner, Hands, 1934 -

Davide Stucchi, Light Switch (Bedroom), 2020

Davide Stucchi, Light Switch (Bedroom), 2020 -

Davide Stucchi, Light Switch (Corridor), 2019

Davide Stucchi, Light Switch (Corridor), 2019 -

Davide Stucchi, Light Switch (Entrance), 2020

Davide Stucchi, Light Switch (Entrance), 2020 -

Davide Stucchi, Light Switch (Sitting room), 2020

Davide Stucchi, Light Switch (Sitting room), 2020 -

Davide Stucchi, Light Switch (Kitchen), 2019

Davide Stucchi, Light Switch (Kitchen), 2019 -

Davide Stucchi, Light Switch (Entrance), 2022

Davide Stucchi, Light Switch (Entrance), 2022 -

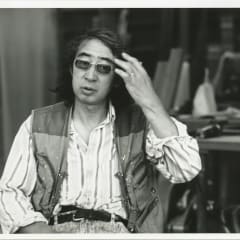

Kishio Suga, Periphery of Space, 1980/2022

Kishio Suga, Periphery of Space, 1980/2022 -

Pol Taburet, Head ||, 2022

Pol Taburet, Head ||, 2022 -

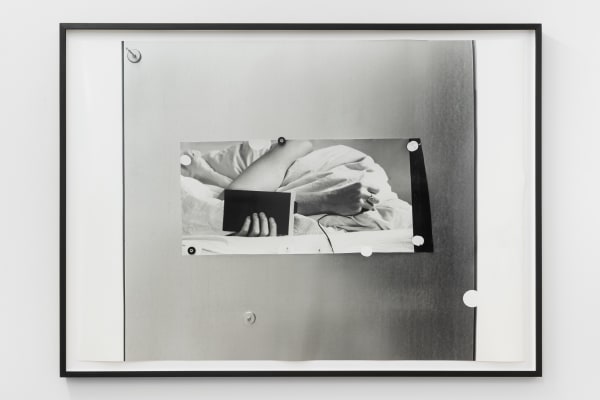

Sophie Thun, (KJ MF MS AG FW LM AS EW) recropped landscape, 2022

Sophie Thun, (KJ MF MS AG FW LM AS EW) recropped landscape, 2022 -

Armando Andrade Tudela, Mano que sostiene, 2012

Armando Andrade Tudela, Mano que sostiene, 2012 -

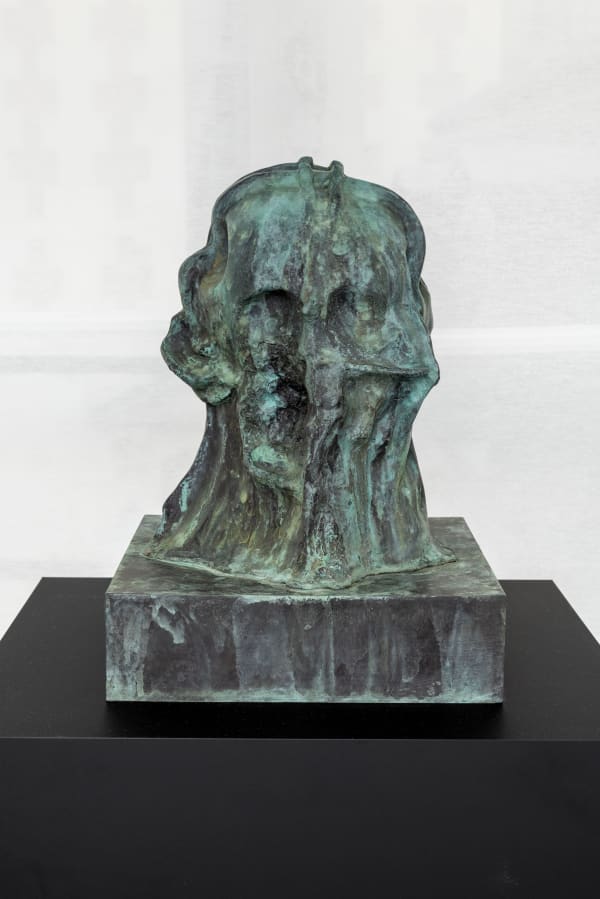

Erika Verzutti, Caverna, 2023

Erika Verzutti, Caverna, 2023 -

Luiz Roque & Erika Verzutti, Contour, 2016

Luiz Roque & Erika Verzutti, Contour, 2016