Veredas Group Show

Past exhibition

Overview

The Under and Over-Mapped: Nonada

Nonada: with this word João Guimarães Rosa opens his seminal novel The Devil to Pay in the Backlands (1956). Contrary to speculation, nonada is an invented word. Portuguese dictionaries describe its as ‘next to nothing’ or ‘pittance’. However, the word can be considered an aiming exercise, where the narrator shoots against a tree. From next to nothing, the author came up with a cardinal, existential and telluric concept, which is ultimately a negotiation with the land for coexistence. Already in the first few pages, Rosa writes: ‘the backlands surround us. These backlands have no size’.

Nonada: the artists exhibited here are also practicing their aim. They are searching far and wide for everything we call image. They are people from the backlands. They have a strong link with Minas Gerais, which is seen here less as an identity and more as a predisposition to moving or crossing. With a distance that is both geological and geographical, several artworks are about the experience with the land. With (dusty) feet and (handwritten) words, Paulo Nazareth (1977) activates the primal sense of crossing a physical and linguistic frontier. Each step is a political and poetic measure. The artist provides silence with a polyglot meaning: his nationality is up for interpretation in the most diverse of American ghettos: is he Latino, Pakistani, African? This form of worldliness from Minas Gerais, which few people have approached, has led to Nazareth transforming the world into an un-world. The artist undoes the world’s virtuality, represented by maps, with his own feet. A master in unveiling meanings in the most elementary things, Nazareth does not hesitate to walk miles in the direction of some lost utopia, presented in works such as Notícias da América [News from America] (2011-2012) and Velha esperança [Old Hope] (2017). This utopia oscillates between land and skin. For instance, À la fleur de la peau exposes the memory of generations printed on the skin and on the images of products, billboards and objects inscribed on the frontiers of peripheral capitalism.

In turn, Solange Pessoa (1961) gives shape to the unconscious of the land. The artist is constantly reinventing origins (Invenção de origem [Origin Invention], 2018), which antecede the invention of Minas Gerais. The artist recreates a No Man’s Land (2015), evoking formations previous to cartography. Prior to the rationale of maps, Pessoa searches time and space looking for a ‘mantic’ and ‘semantic’ dimension of land through a practice that evokes the mysterious aspects of magic. Her work lies in the boundaries between the organic and the inorganic, in the un-definitions of male and female, in the permanent coitus of matter that ignores the humanity that tries to contain and dominate it. The artist arranges matter in a redundant way, bringing together matter and word: stones are stones, fabric is fabric and hair is hair. This ‘coincidence’ produces visions and epiphanies, communicating a form that we can assimilate before we can understand it.

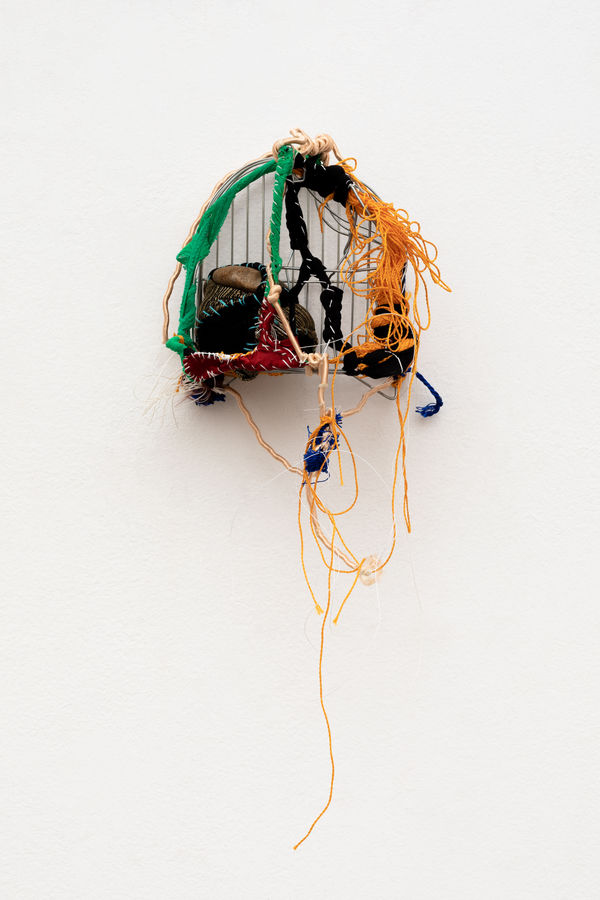

Differently from Solange Pessoa, Sonia Gomes’ (1948) tessituras and twists evoke hybrid bodies. The artist gives shape to invented beings through the assemblage of objects that resemble a combination of different female experiences. Her choice of textiles is astute and the bodies she creates highlight a continuous birth, as in A vida renasce, sempre [Life is Reborn, Always] (2018) or Memória [Memory] (2004).

Patrícia Leite (1955) presents another dimension of depth: the experience of nighttime through painting. She turns painting into a unique experience of the night in a such way that, even when faced with canvases that depict daylight, their limited duration directs us to a coexistence with the stars. From dusk to dawn, Leite finds the exact distance to a starry sky. The artist modulates her representations of the sky: she takes us closer to a lunar landscape (De longe [From Faraway, 2015), to a cathedral’s dome (Italy, 2014), to a lighthouse and artificial light posts. Her representations of stars, circus tents or light displays guide us towards another depth: the depth of constellations.

Also within the experience of light, Amadeo Lorenzato’s (1900-1995) twilight of 1991 evokes the pure act of painting: the cluster of lights suggests a night in a poor neighborhood, which we also see in another painting: Untitled, from 1990. The artist literally combed color, as described by Laymert Garcia dos Santos. This delicate and feminine dimension can be observed throughout the artist’s body of work. After being involved in an accident in 1956, Lorenzato began to devote himself entirely to painting. Self-taught, the artist created landscapes that reveal spirits that are apparently languid but also in harmony with the environment. In Flora e fauna tropical [Tropical Flora and Fauna] (1977), three Black women are lying on the floor. The women, whose skin color matches the tree trunks, appear to be extensions of the tree roots. In another painting from the mid-1970s, a thinker sleeps on the lawn. On the background, at the top, a castle is practically diluted into the sky.

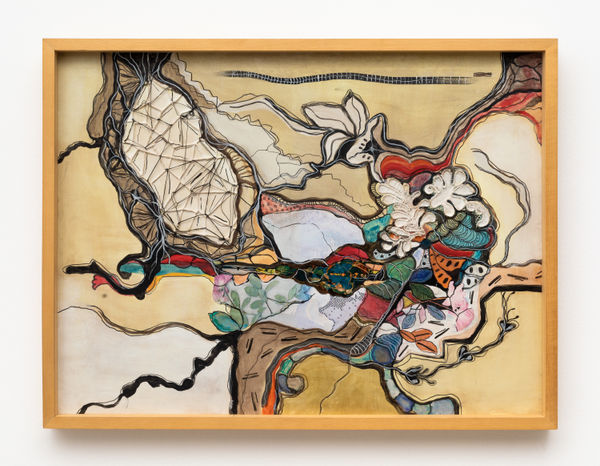

In another perspective of movement, Marina Perez Simão (1981) searches for an aesthetics of fragments, a landscape or something that can be considered post-landscape. In Untitled (2017) we see mist against the trees and a quest for figuration. Details and viewpoints linked to photographic techniques also appear in other paintings produced by Simão, in which the human presence is almost intrusive. Furthermore, the use of diverse materials, such as watercolor and photography, is brought together in a sort of diary that marks the artist’s lyrical gaze.

Going back to Rosa’s pathways, the exhibition features two artists whose sensibilities both differ and complement each other: Amílcar de Castro (1920 – 2002) and Lygia Clark (1920 – 1988). In Castro’s Escultura de corte [Cut Scupture] and Dobra quadrada [Cut Square Fold], both from 1998, we see the realization of a procedure that can be found in one of the poems written by the artist: ‘when I cut and fold/ an iron plate. Or only cut/intend/open a space/ by day-breaking the raw material/ light that veils and unveils/the communion of the opaque/ with the space of stars/ space/ that reveals the rebirthing/ redeeming the heavy matter in the intention to fly’. In Lygia Clark, we see the path itself and the endlessness of Rosa’s backlands. In Composição [Composition] from 1956, the multiplicity of planes and ‘folds’ configure a movement that leads to her later work titled Caminhando [Walking] from 1963. The minutest way of connecting a geometric sensibility to the infinitely minimal. Nonada.

– Eduardo Jorge de Oliveira

Nonada: with this word João Guimarães Rosa opens his seminal novel The Devil to Pay in the Backlands (1956). Contrary to speculation, nonada is an invented word. Portuguese dictionaries describe its as ‘next to nothing’ or ‘pittance’. However, the word can be considered an aiming exercise, where the narrator shoots against a tree. From next to nothing, the author came up with a cardinal, existential and telluric concept, which is ultimately a negotiation with the land for coexistence. Already in the first few pages, Rosa writes: ‘the backlands surround us. These backlands have no size’.

Nonada: the artists exhibited here are also practicing their aim. They are searching far and wide for everything we call image. They are people from the backlands. They have a strong link with Minas Gerais, which is seen here less as an identity and more as a predisposition to moving or crossing. With a distance that is both geological and geographical, several artworks are about the experience with the land. With (dusty) feet and (handwritten) words, Paulo Nazareth (1977) activates the primal sense of crossing a physical and linguistic frontier. Each step is a political and poetic measure. The artist provides silence with a polyglot meaning: his nationality is up for interpretation in the most diverse of American ghettos: is he Latino, Pakistani, African? This form of worldliness from Minas Gerais, which few people have approached, has led to Nazareth transforming the world into an un-world. The artist undoes the world’s virtuality, represented by maps, with his own feet. A master in unveiling meanings in the most elementary things, Nazareth does not hesitate to walk miles in the direction of some lost utopia, presented in works such as Notícias da América [News from America] (2011-2012) and Velha esperança [Old Hope] (2017). This utopia oscillates between land and skin. For instance, À la fleur de la peau exposes the memory of generations printed on the skin and on the images of products, billboards and objects inscribed on the frontiers of peripheral capitalism.

In turn, Solange Pessoa (1961) gives shape to the unconscious of the land. The artist is constantly reinventing origins (Invenção de origem [Origin Invention], 2018), which antecede the invention of Minas Gerais. The artist recreates a No Man’s Land (2015), evoking formations previous to cartography. Prior to the rationale of maps, Pessoa searches time and space looking for a ‘mantic’ and ‘semantic’ dimension of land through a practice that evokes the mysterious aspects of magic. Her work lies in the boundaries between the organic and the inorganic, in the un-definitions of male and female, in the permanent coitus of matter that ignores the humanity that tries to contain and dominate it. The artist arranges matter in a redundant way, bringing together matter and word: stones are stones, fabric is fabric and hair is hair. This ‘coincidence’ produces visions and epiphanies, communicating a form that we can assimilate before we can understand it.

Differently from Solange Pessoa, Sonia Gomes’ (1948) tessituras and twists evoke hybrid bodies. The artist gives shape to invented beings through the assemblage of objects that resemble a combination of different female experiences. Her choice of textiles is astute and the bodies she creates highlight a continuous birth, as in A vida renasce, sempre [Life is Reborn, Always] (2018) or Memória [Memory] (2004).

Patrícia Leite (1955) presents another dimension of depth: the experience of nighttime through painting. She turns painting into a unique experience of the night in a such way that, even when faced with canvases that depict daylight, their limited duration directs us to a coexistence with the stars. From dusk to dawn, Leite finds the exact distance to a starry sky. The artist modulates her representations of the sky: she takes us closer to a lunar landscape (De longe [From Faraway, 2015), to a cathedral’s dome (Italy, 2014), to a lighthouse and artificial light posts. Her representations of stars, circus tents or light displays guide us towards another depth: the depth of constellations.

Also within the experience of light, Amadeo Lorenzato’s (1900-1995) twilight of 1991 evokes the pure act of painting: the cluster of lights suggests a night in a poor neighborhood, which we also see in another painting: Untitled, from 1990. The artist literally combed color, as described by Laymert Garcia dos Santos. This delicate and feminine dimension can be observed throughout the artist’s body of work. After being involved in an accident in 1956, Lorenzato began to devote himself entirely to painting. Self-taught, the artist created landscapes that reveal spirits that are apparently languid but also in harmony with the environment. In Flora e fauna tropical [Tropical Flora and Fauna] (1977), three Black women are lying on the floor. The women, whose skin color matches the tree trunks, appear to be extensions of the tree roots. In another painting from the mid-1970s, a thinker sleeps on the lawn. On the background, at the top, a castle is practically diluted into the sky.

In another perspective of movement, Marina Perez Simão (1981) searches for an aesthetics of fragments, a landscape or something that can be considered post-landscape. In Untitled (2017) we see mist against the trees and a quest for figuration. Details and viewpoints linked to photographic techniques also appear in other paintings produced by Simão, in which the human presence is almost intrusive. Furthermore, the use of diverse materials, such as watercolor and photography, is brought together in a sort of diary that marks the artist’s lyrical gaze.

Going back to Rosa’s pathways, the exhibition features two artists whose sensibilities both differ and complement each other: Amílcar de Castro (1920 – 2002) and Lygia Clark (1920 – 1988). In Castro’s Escultura de corte [Cut Scupture] and Dobra quadrada [Cut Square Fold], both from 1998, we see the realization of a procedure that can be found in one of the poems written by the artist: ‘when I cut and fold/ an iron plate. Or only cut/intend/open a space/ by day-breaking the raw material/ light that veils and unveils/the communion of the opaque/ with the space of stars/ space/ that reveals the rebirthing/ redeeming the heavy matter in the intention to fly’. In Lygia Clark, we see the path itself and the endlessness of Rosa’s backlands. In Composição [Composition] from 1956, the multiplicity of planes and ‘folds’ configure a movement that leads to her later work titled Caminhando [Walking] from 1963. The minutest way of connecting a geometric sensibility to the infinitely minimal. Nonada.

– Eduardo Jorge de Oliveira

Works

-

Patricia Leite, Flores e contas, 2019

Patricia Leite, Flores e contas, 2019 -

Amílcar De Castro, Escultura de Corte e Dobra Quadrada, 1998

Amílcar De Castro, Escultura de Corte e Dobra Quadrada, 1998 -

Solange Pessoa, Untitled, 2012

Solange Pessoa, Untitled, 2012 -

Amadeo Luciano Lorenzato, Untitled | Sem título, 1979

Amadeo Luciano Lorenzato, Untitled | Sem título, 1979 -

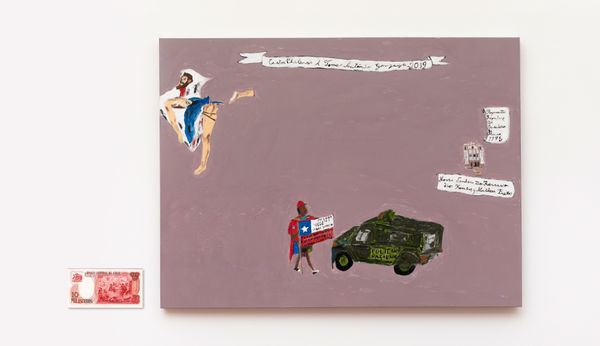

Paulo Nazareth, Cartas Chilenas a Tomas Antonio Gonzaga, 2019

Paulo Nazareth, Cartas Chilenas a Tomas Antonio Gonzaga, 2019 -

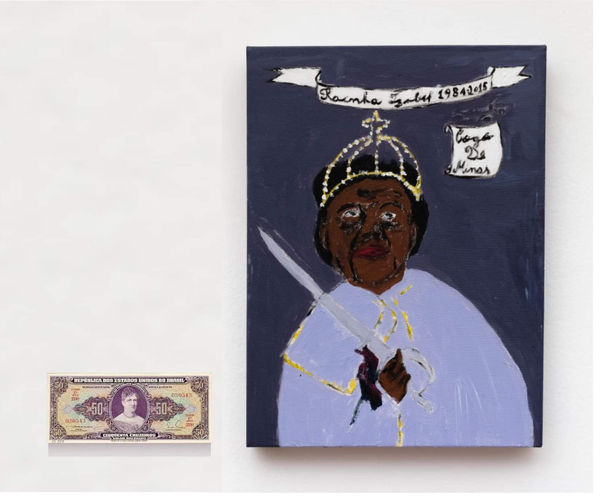

Paulo Nazareth, Rainha Izabel , Congo de Minas 1984 - 2015, 2019

Paulo Nazareth, Rainha Izabel , Congo de Minas 1984 - 2015, 2019 -

Solange Pessoa, Sem título, 1999

Solange Pessoa, Sem título, 1999 -

Celso Renato, Untitled | Sem título, 1988

Celso Renato, Untitled | Sem título, 1988 -

Celso Renato, Untitled, n.d.

Celso Renato, Untitled, n.d. -

Sonia Gomes, Untitled, Ritmo da linha series, 2009

Sonia Gomes, Untitled, Ritmo da linha series, 2009 -

Lygia Clark, Composição , 1956

Lygia Clark, Composição , 1956 -

![Paulo Nazareth, Lei Aurea [ ou Pelourinho ], 2019](data:image/gif;base64,R0lGODlhAQABAIAAAAAAAP///yH5BAEAAAAALAAAAAABAAEAAAIBRAA7) Paulo Nazareth, Lei Aurea [ ou Pelourinho ], 2019

Paulo Nazareth, Lei Aurea [ ou Pelourinho ], 2019 -

Marina Perez Simão, Untitled, 2019

Marina Perez Simão, Untitled, 2019 -

Patricia Leite, Untitled, 2019

Patricia Leite, Untitled, 2019 -

Sonia Gomes, Untitled, 2019

Sonia Gomes, Untitled, 2019 -

Pedro Correia de Araujo

Pedro Correia de Araujo

Installation Views

![Paulo Nazareth, Lei Aurea [ ou Pelourinho ], 2019](https://static-assets.artlogic.net/w_600,c_limit,f_auto,fl_lossy,q_auto,dpr_auto/artlogicstorage/mendeswooddm/images/view/fe1cfd550b0bc06b6b34a1af921805ccj/mendeswooddm-paulo-nazareth-lei-aurea-ou-pelourinho-2019.jpg)