Diálogos do Dia e da Noite Rosana Paulino

Nature and art are two subjects that have fascinated Rosana Paulino from an early age. Drawn to the study of biology, Paulino considered turning her passion into a career but decided instead to follow another lifelong calling to pursue a degree in visual arts. These two systems of knowledge have persisted in her personal and professional life ever since. As an artist, Rosana Paulino has created, investigated, lectured, and written about the presences and absences of Black representation in Brazilian society. Throughout her practice, she has continued to challenge perceptions and re-inscribe history, attributing new roles for Black women in Brazil in particular. Through her art, Paulino has challenged centuries of systematic prejudice that have consistently excluded Afro-Brazilian heritage from public memory. In addition, it has always remained clear to her that it’s inconceivable to consider Black emancipation as detached from an embedded belonging in nature – clear, too, that the construction of an inclusive future is grounded upon ecological awareness and reconnection with natural systems that have been historically severed from marginalized communities.

In Diálogos do Dia e da Noite (Dialogues of the Day and of the Night) the artist presents a series of new paintings, set in nightly or nocturnal environments, that challenge historical subjectivities of Black women. Inspired by the possibilities of nightfall and against a backdrop of dreams, Paulino returns to archetypes, female bastions, goddesses or guides, many of which emerge from her ongoing series Senhora das Plantas. This time, these women-like figures with limbs sprawling into tree roots, hair growing as leaves, or fingers blossoming into flowers, stand, crawl, or kneel in darkness. Emerging at night, they confront viewers with the mysteries that exist in the darkest hours, forming a botanical mythos that is at once attractive and deceiving.

The plants, weeds, and flowers that grow from and within the paintings of the exhibition are found abundantly in gardens throughout Brazil. Most importantly, they are widely known for their social, cultural, and spiritual connotations, which blossom beyond the field of Western scientific practices. Their leaves and bushes have been planted perennially as elements of protection, some of them cultivated in gardens and on porches to cast away evil spirits, others used in baths or amulets to call upon protection. It is in often-undocumented sources of knowledge that Paulino harvests the inspiration that guides her pencil freely and nurtures her art form.

The large, lush tropical plant Comigo ninguém pode (dumb cane), which sprawls across indoor or outdoor terraces, is notoriously mischievous in nature. The pride of many gardeners, it is also incredibly toxic if consumed by animals or humans alike. Its Portuguese common name is a self-proclaimed affirmation, which literally translates to the claim “with me, nobody can [mess],” truthful to the plant’s protective powers. Paulino presents various versions of this deceiving vegetation in a series of improbable plant-devouring figures, Comingo ninguém pode No 1, No 2, and No 3 (all 2024), culminating in the large, imposing painting set against the dark. In this last representation, vines and leaves shoot from the figure’s fingers, breasts, mouth, and even assume the form of eyes, as womankind and plant take a single form. It is through such strong visual affirmations that Paulino creates a powerful ecosystem of ideas that is resolutely feminine and contemporary.

Walking the line between enchantment and peril is a series of works portraying the mystically named trombeta de anjo (angel’s trumpet). Its seductive appearance and divine-sounding description mask the flower’s inherit toxicity, blurring the lines between healing and harm, or vision and death. In both a new painting and a dry pastel work on paper, long, drooping, sensual flowers create an almost theatrical scene with their bearer. Paulino is fascinated by the symbolism of a flower that both dreams and deceives, recognizing nature’s fantastical capacity for survival, something she identifies in the resilience of Black women throughout time, adapting to thrive.

Ambiguity is also embodied in the sword-like espada de Iansã (sword of Iansã), a plant synonymous with strength and protection. They adorn the heads and hands of fearless creatures that inhabit the exhibition. Yet, once again, the species’s positive perception is overpowered by inherent toxicity, making it extremely dangerous and even lethal if misused. In this layered garden, Paulino cultivates an oneiric universe with elements that bring forward the dangerous nature of resistance. Other living creatures such as birds and crows fly or lay around the bodies of these nocturnal figures, bringing with them new knowledge.

Drawing lies at the center of the artist’s practice. Her notebooks, containing pages of sketches and observations, have gradually been incorporated as key artworks in her exhibitions. In New York, they are presented as poetic sketches, such as Estudo para Comigo ninguém pode (2024) or Estudo para plantas (2024), which later emerge as the central paintings within the exhibition. Observing them is as if uncovering the visual diary of the artist, whose practice can also be described as an ever- evolving network of reflections, cataloging emancipatory thoughts as a vow of responsibility. Finally, the exhibition foregrounds themes that drive her ongoing commitment to denouncing systems of exclusion. This arises in prior works such as the collage As Filhas de Eva (2014) or the mixed media work Três Vezes Coração (2024) which bring to light centuries of institutionalized discrimination, which continuously pass through frameworks of representation.

Beyond the exhibition on view at Mendes Wood DM’s Tribeca gallery space, The Creation of the Creatures of Day and Night (2024), an imposing commission by the artist, is currently exhibited at New York’s High Line. The large-scale mural overlooking the public park is a continuation of Paulino’s mangrove series, in which her tree-woman figures spread their roots out to this complex ecosystem, reclaiming their existence. As Paulino’s distinctive pantheon of female guardians and botanical creatures traverses gallery walls and public spaces, we confront vital questions: How do these figures shift our gaze, and what remedies and transformations might they enact in our world?

-

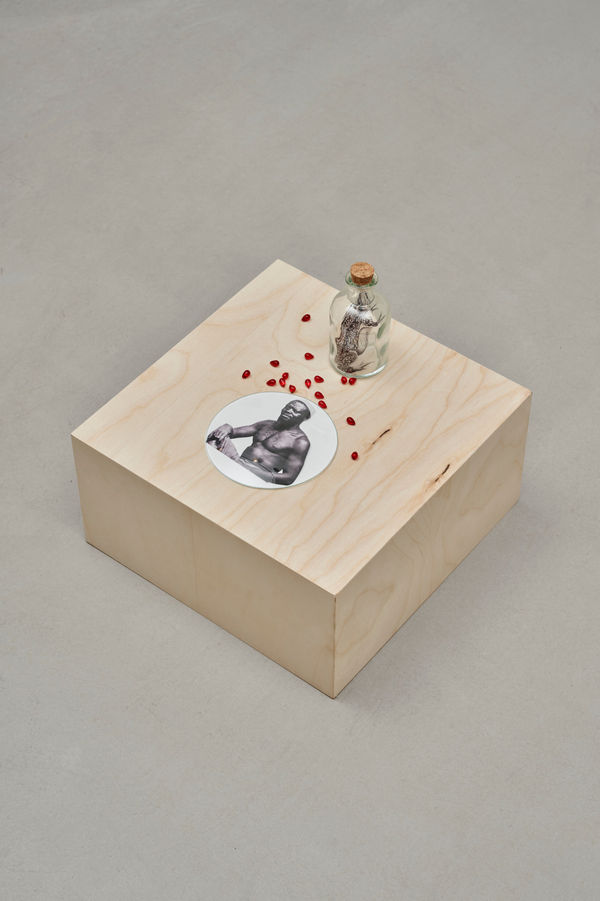

Rosana Paulino, Untitled | Sem Título, 2025

Rosana Paulino, Untitled | Sem Título, 2025 -

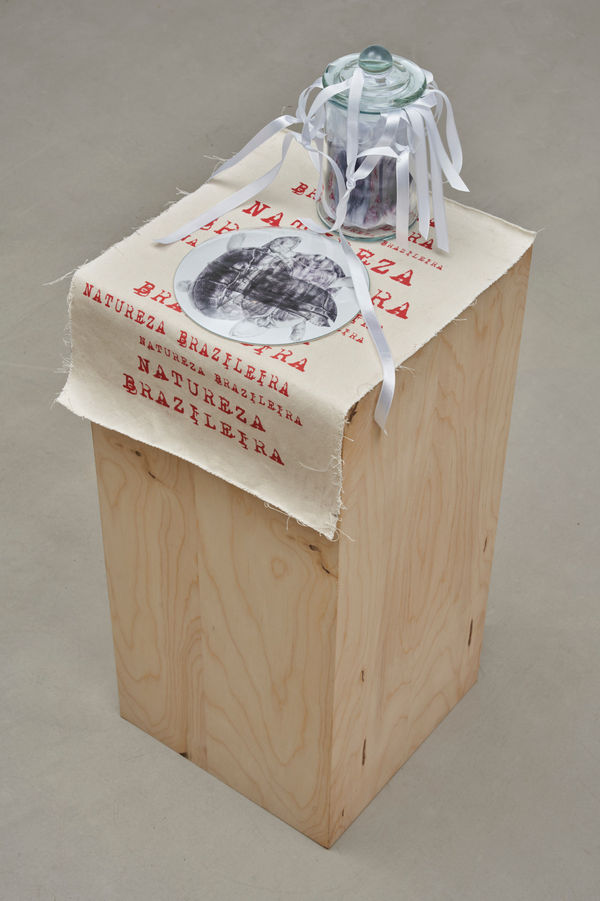

Rosana Paulino, Binding to save the life of those without a soul | Amarração para salvar a vida para dos que não tem alma, 2025

Rosana Paulino, Binding to save the life of those without a soul | Amarração para salvar a vida para dos que não tem alma, 2025 -

Rosana Paulino, Untitled | Sem Título, 2025

Rosana Paulino, Untitled | Sem Título, 2025 -

Rosana Paulino, Untitled | Sem Título, 2025

Rosana Paulino, Untitled | Sem Título, 2025 -

Rosana Paulino, Untitled | Sem Título, 2025

Rosana Paulino, Untitled | Sem Título, 2025 -

Rosana Paulino, Three Times the Heart | Três Vezes Coração, 2024

Rosana Paulino, Three Times the Heart | Três Vezes Coração, 2024 -

Rosana Paulino, Untitled | Sem Título, 2025

Rosana Paulino, Untitled | Sem Título, 2025 -

Rosana Paulino, Cow's Foot | Pata de vaca, 2022

Rosana Paulino, Cow's Foot | Pata de vaca, 2022 -

Rosana Paulino, Study for comigo ninguém pode | Estudos para comigo ninguém pode, 2024

Rosana Paulino, Study for comigo ninguém pode | Estudos para comigo ninguém pode, 2024 -

Rosana Paulino, Untitled | Sem Título, 2025

Rosana Paulino, Untitled | Sem Título, 2025 -

Rosana Paulino, Untitled | Sem título, 2025

Rosana Paulino, Untitled | Sem título, 2025 -

Rosana Paulino, Untitled | Sem título, 2025

Rosana Paulino, Untitled | Sem título, 2025 -

Rosana Paulino, Untitled | Sem Título, 2025

Rosana Paulino, Untitled | Sem Título, 2025 -

Rosana Paulino, Study for comigo ninguém pode | Estudos para comigo ninguém pode, 2024

Rosana Paulino, Study for comigo ninguém pode | Estudos para comigo ninguém pode, 2024 -

Rosana Paulino, Untitled | Sem Título, 2025

Rosana Paulino, Untitled | Sem Título, 2025 -

Rosana Paulino, Untitled | Sem Título, 2025

Rosana Paulino, Untitled | Sem Título, 2025 -

Rosana Paulino, Untitled | Sem título, 2025

Rosana Paulino, Untitled | Sem título, 2025 -

Rosana Paulino, Untitled | Sem Título, 2025

Rosana Paulino, Untitled | Sem Título, 2025 -

Rosana Paulino, Senhora das Plantas, 2025

Rosana Paulino, Senhora das Plantas, 2025 -

Rosana Paulino, Senhora das Plantas, 2025

Rosana Paulino, Senhora das Plantas, 2025 -

Rosana Paulino, Comigo Ninguém pode N°3, from the series Senhora das Plantas | Comigo Ninguém pode N°3, da série Senhora das Plantas, 2024

Rosana Paulino, Comigo Ninguém pode N°3, from the series Senhora das Plantas | Comigo Ninguém pode N°3, da série Senhora das Plantas, 2024 -

Rosana Paulino, Angel's Trumpet, from the series Senhora das Plantas | Trombeta de Anjo, da série Senhora das Plantas, 2025

Rosana Paulino, Angel's Trumpet, from the series Senhora das Plantas | Trombeta de Anjo, da série Senhora das Plantas, 2025 -

Rosana Paulino, Comigo ninguém pode, from senhora das plantas series | Comigo ninguém pode, da série senhora das plantas, 2024

Rosana Paulino, Comigo ninguém pode, from senhora das plantas series | Comigo ninguém pode, da série senhora das plantas, 2024 -

Rosana Paulino, Untitled | Sem título, 2024

Rosana Paulino, Untitled | Sem título, 2024 -

Rosana Paulino, Untitled | Sem título, 2024

Rosana Paulino, Untitled | Sem título, 2024 -

Rosana Paulino, Sem título (da série Pássaro da Noite) | Untitled (from the Night Bird series), 2024

Rosana Paulino, Sem título (da série Pássaro da Noite) | Untitled (from the Night Bird series), 2024 -

Rosana Paulino, Angel's trumpet, from the series Senhora das Plantas | Trombeta de Anjo, da série Senhora das Plantas, 2024

Rosana Paulino, Angel's trumpet, from the series Senhora das Plantas | Trombeta de Anjo, da série Senhora das Plantas, 2024 -

Rosana Paulino, Untitled | Sem título, 2025

Rosana Paulino, Untitled | Sem título, 2025 -

Rosana Paulino, Comigo Ninguém Pode (da série Senhora das Plantas) | Comigo Ninguém Pode (from Senhora das Plantas series), 2025

Rosana Paulino, Comigo Ninguém Pode (da série Senhora das Plantas) | Comigo Ninguém Pode (from Senhora das Plantas series), 2025 -

Rosana Paulino, Angel's trumpet, da série Senhora das Plantas | Trombeta de Anjo, da série Senhora das Plantas, 2024

Rosana Paulino, Angel's trumpet, da série Senhora das Plantas | Trombeta de Anjo, da série Senhora das Plantas, 2024 -

Rosana Paulino, Study for comigo ninguém pode | Estudo para comigo ninguém pode, 2024

Rosana Paulino, Study for comigo ninguém pode | Estudo para comigo ninguém pode, 2024 -

Rosana Paulino, Untitled | Sem título, 2025

Rosana Paulino, Untitled | Sem título, 2025 -

Rosana Paulino, Angel's trumpet, from the series Senhora das Plantas |Trombeta de Anjo, da série Senhora das Plantas, 2025

Rosana Paulino, Angel's trumpet, from the series Senhora das Plantas |Trombeta de Anjo, da série Senhora das Plantas, 2025 -

Rosana Paulino, Untitled | Sem título, 2025

Rosana Paulino, Untitled | Sem título, 2025 -

Rosana Paulino, Untitled | Sem Título, 2025

Rosana Paulino, Untitled | Sem Título, 2025 -

Rosana Paulino, Daughters of Eve | As Filhas de Eva, 2014

Rosana Paulino, Daughters of Eve | As Filhas de Eva, 2014 -

Rosana Paulino, Daughters of Eve | As Filhas de Eva, 2014

Rosana Paulino, Daughters of Eve | As Filhas de Eva, 2014 -

Rosana Paulino, Three times the heart | Três vezes o coração, 2024

Rosana Paulino, Three times the heart | Três vezes o coração, 2024 -

Rosana Paulino, The progress of nations | O progresso das nações, 2021

Rosana Paulino, The progress of nations | O progresso das nações, 2021