arrastar chãos, juntar imbigos Josi

It is a process that unfolds in the movement of gestures, in the creations operated by hand, and thus, make themselves felt as hands. They collect the grains of earth, which come together and disperse, sticking to where they pass or dissipate. They pass through the sieve, remain in the sieve. They go to the mortar. They decant, ask for patience, pass through time as well. They go to the pan and spin. Until everything is there, for the eyes of those who know how to see: the color of the ground, at ground level. To the keen criteria of the senses, whilst everything happens, grounding, thickening, until almost nothing is touched, besides life itself. Kneading, watering, raising - a stubbornness. Smoothing, making it shine. Fire and an uncertain destiny. Art, bordering on life, is the path, the way, moving with the earth, which comes from times and vibrations of the world, from before the world was what we think we know. The element of art is, then, the gesture with the earth. Touching life - living beings of clay, the traces of everything that is kept in it. Sensing the times - including geological times, respecting the rhythms of the earth - and practicing them in the materials. Acknowledging crossings as part of its history, from those who took steps before yours. These are experiences that intertwine with Josi's artistic gestures.

The weaving of her works occurs in her hands and comes from everything that magnetizes in the musculature of the hands' doing, in a kind of dilation or differentiation that deviates from already so proliferated canons, which have become comfortable instances of aesthetic judgment. In this process, a poetic fold seems to reveal itself: A body that is born with the body of matter. Josi creates spaces for the body to fill itself and with the earth, whose genesis are shared, compacted, synchronous. A collective and ancestral self and earth where confluences germinate, "a force that yields, that increases, that expands," where "we become people and other people," as the writer, professor, quilombola leader, and political activist Nêgo Bispo tells us. Creating, for Josi, is a "movement," in resonance, in confluence with the earth and the place(s) of origin, with what sprouts in/from the places, as a practice that seems to intensify outside the language and that is stripped of the tired grammars of contemporary art, which pretend to be universal and omnipresent.

From the sketches made in notebooks during bus rides to the dream that art (despite everything) is not a privilege; from experiences in Itamarandiba, Carbonita, and Caeté to life as a teacher; from so much wisdom kept along with the washing of clothes and the daily toil in the fields to a degree in Fine Arts at the Guignard School (UEMG); from the dirt floors of Tabatinga to the floor of the kitchen/studio; from these places that do not separate into borders but gather together, because they are, at the same time, memory and an agglomeration of times, Josi becomes an artist. In these overlaps of times, places, and braided narratives, the inks were being acknowledged while the water boiled for the beans, the fruit stains were suddenly pigmenting the surfaces, and the muddy water formed earth and ground tones.

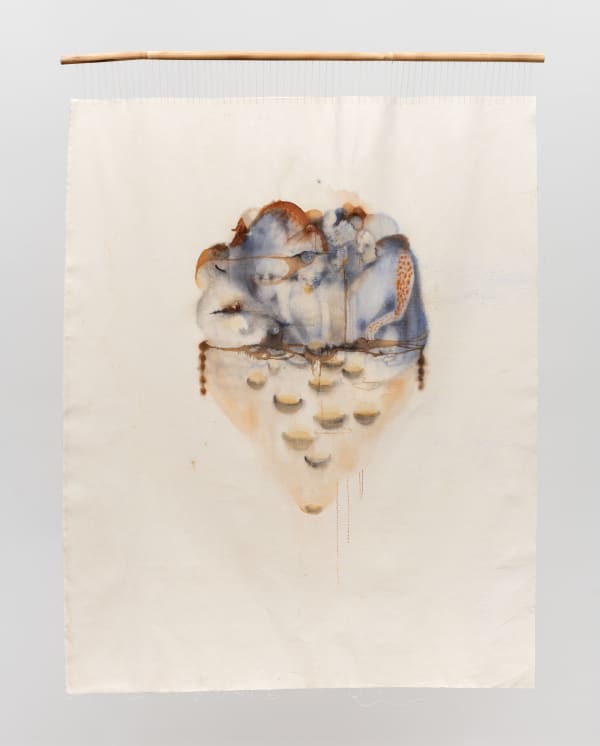

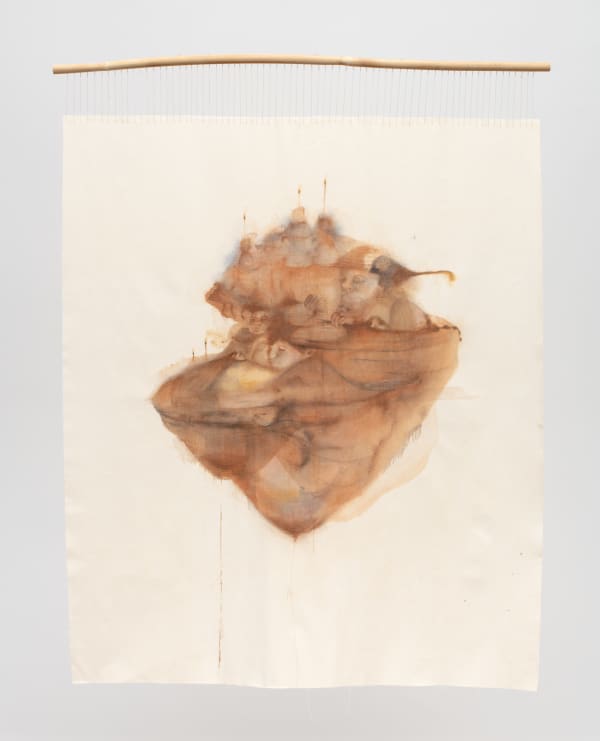

With these materials and the gestures created in this coexistence, her painting process involves meticulous waiting for the events that these pigments create. On the canvas, they reveal themselves in spreads, veils, concentrations, dissolutions, disappearances, transparencies, glazes, empty spaces, and color changes. There is no prior drawing, “no previous risk,” as she explains, because there is no way to stop or control what is not anticipated to happen. Josi says she seeks a “curvature of color,” but the time of each pigment is an experience that distinguishes itself on paper and fabric while she paints and, therefore, the pigments interact in different ways, dialoguing with humidity, with temperature, according to the composition of organic paints (more or less aqueous). There are also no lines. Lines separate. The stains proliferate, are tributaries on the canvas, overlap, move, and occupy spaces. Then, it is another time, another color, they resurface in other images.

Josi approached clay because it can be understood as a bit of soil that “walked from a rock, met the wind, the rain, and other beings and then went to sediment, carrying along all that memory.” In her hands, the clay, which arrives like a “treasure,” meets again the throat that drank pot water, to then receive the gestures of touching, kneading, shaping. The low fire is what dictates what it will become. Dealing with clay is conversing with the tradition of making utensils present in daily life and with the ancestralities and memories of the time when stepping on the ground was having that ground always present in life. Exile is the opposite: it is not having a place to step, it is relearning to walk, and, therefore, almost undoing oneself from the longing for the people who once inhabited the ground and got lost.

In Josi’s ceramics, there are faces, encounters of human figures, contiguous bodies, tool and body being one thing, and, from there, figuration is a shelter that materializes the desire to populate life with presences, to recount other fables than that of exile. In these sculptures, togetherness, community building, and stories that didn’t happen narrate a place that the body didn’t have the right to, because emptiness and dispersion commanded the flow of life. “It’s where I gather myself whole,” says the artist. And again, dealing with clay: A learning and also an imaginary that Josi brings from the Jequitinhonha Valley – from people together, from conversations, from the daily work, from the “imbilical” cords sun drying, mixing with the earth. Touching this life in clay is gathering presences, reversing erasures, enunciating ancestral knowledge.

arrastar chãos, juntar imbigos is the title of Josi’s first solo exhibition, in which the works are brought together by the same procedures of touching, dragging, gathering, so present in her craftsmanship. A gathering of times, materials, people, stories, everything that reminds us that art “is a conversation of souls because it goes from the individual to communitarianism, as it is shared” – once again Nêgo Bispo tells us about the difference between exchange and sharing. And thus, they invite us to practice other ways of seeing and making life and sustenance. These creations are here to affirm the presences of people who were expropriated from their gestures and living together, separated from their environment (what civility calls nature), who were tasked with overcoming (as a challenge, a fate, an obligation) the oppressions of being far and without a place. The presences of people who resist the wars of colonialist denominations, creating relationships with every being and with the earth, which is the “original yearning.”

– Galciani Neves

Josi (b. 1983, Itamarandiba, Brazil) lives and works in Belo Horizonte.

Recent exhibitions include Imagens que não se conformam, Memorial Minas Vale (2023), Linhas Tortas, Mendes Wood DM São Paulo (2023), Ensaios para o Museu das Origens, Instituto Tomie Ohtake (2023), O corpo invisível da memória, Museu da Inconfidência de Ouro Preto (2023), Six Artists, Mendes Wood DM New York (2023), Prêmio PIPA, Paço Imperial (2022).

-

Josi, Sem título, da série: decantações, fervuras e temperamentos - Untitled, from the series: decantations, boils and temperaments, 2022

Josi, Sem título, da série: decantações, fervuras e temperamentos - Untitled, from the series: decantations, boils and temperaments, 2022 -

Josi, Sem título, da série: decantações, fervuras e temperamentos - Untitled, from the series: decantations, boils and temperaments, 2022

Josi, Sem título, da série: decantações, fervuras e temperamentos - Untitled, from the series: decantations, boils and temperaments, 2022 -

Josi, Sem título, da série: decantações, fervuras e temperamentos - Untitled, from the series: decantations, boils and temperaments, 2023

Josi, Sem título, da série: decantações, fervuras e temperamentos - Untitled, from the series: decantations, boils and temperaments, 2023 -

Josi, Sem título, da série: decantações, fervuras e temperamentos - Untitled, from the series: decantations, boils and temperaments, 2023

Josi, Sem título, da série: decantações, fervuras e temperamentos - Untitled, from the series: decantations, boils and temperaments, 2023 -

Josi, Sem título, da série: decantações, fervuras e temperamentos - Untitled, from the series: decantations, boils and temperaments, 2022

Josi, Sem título, da série: decantações, fervuras e temperamentos - Untitled, from the series: decantations, boils and temperaments, 2022 -

Josi, Sem título, da série: decantações, fervuras e temperamentos - Untitled, from the series: decantations, boils and temperaments, 2022

Josi, Sem título, da série: decantações, fervuras e temperamentos - Untitled, from the series: decantations, boils and temperaments, 2022 -

Josi, girino curralinho, from the series: quara-dores | girino curralinho, da série: quara-dores, 2024

Josi, girino curralinho, from the series: quara-dores | girino curralinho, da série: quara-dores, 2024 -

Josi, Sem título, da série: Receitas de nódias e máculas - Untitled, from the series: Recipes for knots and stains, 2024

Josi, Sem título, da série: Receitas de nódias e máculas - Untitled, from the series: Recipes for knots and stains, 2024 -

Josi, da série: chão de molho e imbigos | from the series: soaked floor and bellybuttons, 2024

Josi, da série: chão de molho e imbigos | from the series: soaked floor and bellybuttons, 2024 -

Josi, da série: chão de molho e imbigos | from the series: soaked floor and bellybuttons, 2024

Josi, da série: chão de molho e imbigos | from the series: soaked floor and bellybuttons, 2024 -

Josi, da série: chão de molho e imbigos | from the series: soaked floor and bellybuttons, 2024

Josi, da série: chão de molho e imbigos | from the series: soaked floor and bellybuttons, 2024 -

Josi, da série: chão de molho e imbigos | from the series: soaked floor and bellybuttons, 2024

Josi, da série: chão de molho e imbigos | from the series: soaked floor and bellybuttons, 2024 -

Josi, da série: chão de molho e imbigos | from the series: soaked floor and bellybuttons, 2024

Josi, da série: chão de molho e imbigos | from the series: soaked floor and bellybuttons, 2024 -

Josi, da série: chão de molho e imbigos | from the series: soaked floor and bellybuttons, 2024

Josi, da série: chão de molho e imbigos | from the series: soaked floor and bellybuttons, 2024 -

Josi, da série grão de água, gota de terra | from the series grains of water, drops of earth, 2024

Josi, da série grão de água, gota de terra | from the series grains of water, drops of earth, 2024 -

Josi, da série grão de água, gota de terra | from the series grains of water, drops of earth, 2024

Josi, da série grão de água, gota de terra | from the series grains of water, drops of earth, 2024 -

Josi, Penerei fubá, from the series: abrigos | Penerei fubá, da série: abrigos, 2023 - 2024

Josi, Penerei fubá, from the series: abrigos | Penerei fubá, da série: abrigos, 2023 - 2024 -

Josi, engole vento, from the series: rastapé | engole vento, da série: rastapé, 2024

Josi, engole vento, from the series: rastapé | engole vento, da série: rastapé, 2024 -

Josi, murundu, from the series: rastapé | murundu, da série: rastapé, 2024

Josi, murundu, from the series: rastapé | murundu, da série: rastapé, 2024 -

Josi, oleira, from the series: rastapé | oleira, da série: rastapé, 2024

Josi, oleira, from the series: rastapé | oleira, da série: rastapé, 2024 -

Josi, inunda, from the series: isca de chão | inunda, da série: isca de chão, 2024

Josi, inunda, from the series: isca de chão | inunda, da série: isca de chão, 2024 -

Josi, olor da lama, from the series: isca de chão | olor da lama, da série: isca de chão, 2024

Josi, olor da lama, from the series: isca de chão | olor da lama, da série: isca de chão, 2024 -

Josi, suor da faina, from the series: isca de chão | suor da faina, da série: isca de chão, 2024

Josi, suor da faina, from the series: isca de chão | suor da faina, da série: isca de chão, 2024 -

Josi, odor da chama, from the series: isca de chão | odor da chama, da série: isca de chão, 2024

Josi, odor da chama, from the series: isca de chão | odor da chama, da série: isca de chão, 2024