Hudson Bathers Matthew Lutz-Kinoy

Past exhibition

Overview

Mendes Wood DM New York

Apr 30 - Jun 15, 2019

Apr 30 - Jun 15, 2019

Mendes Wood DM is pleased to announce Hudson Bathers, an exhibition of new work by Matthew Lutz-Kinoy.

For his first show at Mendes Wood DM in New York, Matthew Lutz-Kinoy fills the gallery with canvases that line the walls and ceiling like the boiseries (painted wooden wall panels) that adorn the Boucher and Fragonard cabinets several blocks away at the Frick. These rooms have served as inspiration for the artist before: the performative figures in his large-scale canvases seem, like Boucher’s infants and Fragonard’s lovers, to inhabit landscapes of diaphanous and luminous colors that spill forth from centers with no horizons, where they act out playful narratives of suggestive content. At Mendes Wood DM, these landscapes are infiltrated by wild beasts that appear to have wandered into the painted panels as if they were invading garden plots and trampling them into threatening forests (think boiseries: the woods behind the wooden wainscoting).

Drawing the animals from the nineteenth-century exotic and from imperialist fantasies of artists like Horace Vernet or Delacroix, Lutz-Kinoy couples them here with limpid human figures whose distinct lack of individual expression finds a projective foil in the externalized expression of their mammal partners. A bather of ambiguous gender clutches at a white cloth while a tiger ferociously slurps the water from which they emerge. Their bodies intertwine, the tiger’s tail mimicking the form of the bather’s peshtemal - or vice-versa - yet there appears to be no active emotional connection between the two. A distance separates the human from the animal, such that the expressive jolt of the animal content becomes diffused and revealed as a screen of emotional projection.

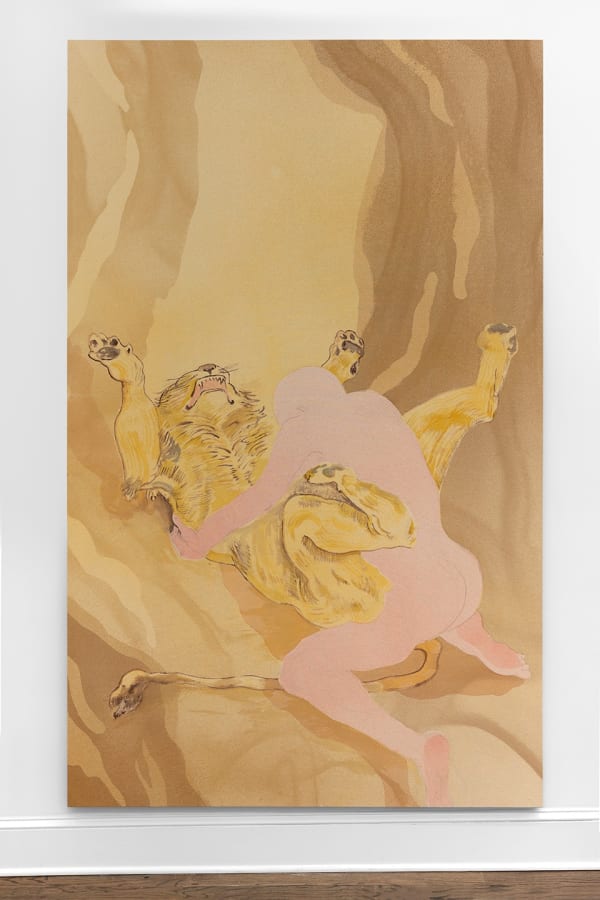

Two paintings take up Fragonard’s so-called La Gimblette explicitly in ways that highlight this affected distancing of subject through repetition. In one (La Gimblette Double), the figure “playing” with a lap dog in a lap-like canopy bed repeats one on top of the other, as if to emphasize the blank artificiality of the scene rather than its primal caress. Likewise, in another painting (Financier) of a human penetrating a lion in missionary position (the pun may well be intentional, pointing to the colonial “mission civilatrice” undergirding certain strands of French exoticism), the human figure is silhouetted, back to front in blank expression. Yet its predatory force seems strangely diffused in spite of the depiction of interspecies copulation: The lion’s tail extends limply from underneath the human’s ass, like an extended tassel pointing out of the image; empire short circuit.

Stranded in front of a gaping, uterine cave (Fragonard’s cavernous lit à la Polonaise reappears), the lion and the human pairing thereby point indirectly to ways in which the pictorial use of animals as ciphers for human emotion hints at a dependence on others to externalize a desire for affective reassurance that the world is indeed ordered in ways that are familiar in ideological terms. This is the allegorical function that animal painting traditionally served in the west, be it in popular eighteenth-century animal painters like Jean-Baptiste Oudry, or Frans Snyders’ monumental seventeenth-century Flemish still lives where narratives of political economy stage transpose themselves into scenes of animal interaction that offer themselves to the viewer like natural commodities to be plucked and enjoyed. These scenes of vulnerable externalization dominate the first room of the exhibition. The figures - made with drawn stencils that have been hosed with colors on the ground with a liberated industrial gardening sprayer (!) - inhabit rectangles like French parterres (flower beds) gone wild with color field staining, their geometric patterned sections guiding the landscape admirers inside and outside of the paintings.

Proceeding into the exhibition’s second room, the meaning shifts subtly as a threshold is crossed from exclamatory exteriorization to a more interior tone. In a long, frieze-like take on the Swiss symbolist Ferdinand Hodler’s Love (1907-1908), Lutz-Kinoy pairs more figures in ambiguous embraces. The animals have departed and Hodler’s heterosexual pairs find themselves stranded in a space from which the horizon has been removed, and gender rendered more fluid: as the work’s title proclaims Love with other people. The couples here, beached with no distance point, inhabit a space of no escape. They will not swim to metaphysical horizons, like Hodler’s lovers on the banks of Lake Geneva, but instead slumber, grappling with one another in the pleasure of dreaming in pink sand. Above them, on the ceiling, hangs a suggestive set of orchids that resemble the genitals of bees (Orchids lure bees with promise of sex with strangers). In the rococo period, the bees would have immediately been recognizable as related to Bernard Mandeville’s Fable of the Bees (1714), in which the collective hive serves as an economic model, embodying the virtues of the division of labor and the prosperity enabled by individual consumption. The faith that the poem placed in the construction of a robust interior persona through the mechanisms of a promiscuous marketplace (legible as so many exteriors that flaunted consumer acuity) laid the basis for a cult of performative “personality” as a form of social and civic engagement.

In Lutz-Kinoy’s show the personalities of the paintings’ protagonists appear, however, to develop only through a fittingly performative dialogue with their animal interlocutors. Or with their shadows and other doubles: in a further work (Six bathers with shadows) grey monochrome figures repose on a pink rectangular ground that spreads beneath them like a giant blanket, or delineated field of action. Between this ground and the figures are white shapes that bring the ground of the canvas to the surface. These shapes are also shadows, intertwined with the posing bodies, although the bodies appear to emerge from these blank forms as much as they seem to cast them. These particular figures are, like Hodler’s lovers, ghostly bathers. They may have wandered out of the Hudson River and, specifically, Alvin Baltrop’s 1970s and 80s black and white photographs of cruising along Manhattan’s Piers. As Glenn O’Brien notes in his text on Baltrop’s images, there were 99 piers then, composed of crumbling metal and concrete that became a stage-like ground where passengers of ships-no-longer-sailing could satisfy their still illegal desire for company, gathering on the jetties and industrial debris of a waning maritime empire (one may be reminded of the Hudson School painter Thomas Coles’ painting cycle of inevitable decline, The Course of Empire, designed for and still hanging in Manhattan). Rather than offering introspective depth, Lutz-Kinoy’s enmeshed doubles of figure and ground highlight the sense of the works as painterly, theatrical backdrops across which both the images’ protagonists and the viewer (all bathers) follow potential paths of interaction together on grounds that are both delicately playful and threatening. Curtains on New York.

–Sasha Rossman

Works

-

Matthew Lutz-Kinoy, La Gimblette double, 2019

Matthew Lutz-Kinoy, La Gimblette double, 2019 -

Matthew Lutz-Kinoy, Financier

Matthew Lutz-Kinoy, Financier -

Matthew Lutz-Kinoy, French horses fighting in stable, 2019

Matthew Lutz-Kinoy, French horses fighting in stable, 2019 -

Matthew Lutz-Kinoy, Six bathers with shadows, 2019

Matthew Lutz-Kinoy, Six bathers with shadows, 2019 -

Matthew Lutz-Kinoy, Orchids lure bees with promise of sex with strangers, 2019

Matthew Lutz-Kinoy, Orchids lure bees with promise of sex with strangers, 2019 -

Matthew Lutz-Kinoy, Love with other people, 2019

Matthew Lutz-Kinoy, Love with other people, 2019

Installation Views