Galáxias Patricia Leite & Leticia Ramos

Cai uma noite sem fim onde se forma, agora, Galáxias, exposição de Patricia Leite e Leticia Ramos. As duas artistas apresentam, nestas salas, imagens e situações que representam ou evocam céus e fenômenos astronômicos. São pinturas, fotografias, vídeos e uma instalação, que dão a ver nuvens, constelações, a lua, eclipses, crepúsculos, planisférios. No conjunto, há obras produzidas em 2017 e 2018, mas a grande maioria foi concebida este ano e para esta mostra, por cada uma delas e pelas duas juntas. É a primeira vez que ambas se unem para uma colaboração autoral. E um dos aspectos dessa parceria que desperta curiosidade, de imediato, é o agrupamento de obras e percursos, à primeira vista, tão distintos.

Patricia Leite começou sua trajetória em meio à euforia pictórica da década de 1980, com uma pintura enérgica, abstrata e com inclinação expressionista, marcada por gestos e cores intensos. A partir de 2000, a artista dá uma guinada no curso de sua produção, rumo a uma figuração simples e sintética, na qual prevalecem paisagens delineadas por enquadramentos incomuns, que levam suas vistas para mais ou para menos perto do abstracionismo. Sobretudo porque Patricia tende a resumir seus motivos a figuras chapadas de cor, com uma fatura franca, sem truques, que por vezes faz que seus elementos pareçam, na composição, os componentes de uma colagem. Desde meados da década de 2000, a artista também experimenta possibilidades diferentes de levar seu pensamento pictórico para outros formatos além do retângulo, para objetos corriqueiros, como as gamelas, e para outras materialidades, como a dos fios tramados da tecelagem.

A produção de Leticia Ramos, por sua vez, começou a obter projeção pública no final daquela mesma década de 2000, ao apresentar trabalhos cujo andamento se dá por meio de projetos, em vez da realização de obras avulsas e variadas. Formada em cinema, após ter cursado arquitetura e urbanismo, Ramos prepara planos de ação com desenvolvimento e execução de médio e longo prazos (por meses, anos), que envolvem processos diversos: desde a realização de pesquisas históricas e científicas (por exemplo, sobre o terremoto de Lisboa em 1775, ou sobre os métodos criados por Hercule Florence, um dos pioneiros da fotografia, para observação do céu e a representação de nuvens); passando pela elaboração de cenários e maquetes para a representação de lugares, objetos e fenômenos naturais, existentes, registrados historicamente ou inventados; até a construção ou adaptação do aparato técnico que produzirá suas imagens em papel fotográfico e filmes. Cada projeto requer, por consequência, a lida com linguagens, áreas do conhecimento e meios de formalização específicos.

Uma natureza experimental talvez ligue, dessa maneira, as duas obras. No entanto, logo se destaca de novo, nesse cotejamento, o contraste entre, de um lado, a afetividade que se verifica nas pinturas de Patricia Leite, sobretudo pela intensidade sensorial que ela busca na relação com seus motivos, e, de outro, o aspecto científico que marca a produção de Leticia Ramos. Patricia parece trazer os elementos que figura para o primeiríssimo plano de suas pinturas, para perto dos olhos de quem os vê, por mais que tais referentes se ponham distantes no espaço, por mais que seus motivos sejam corpos celestes; ao passo que Ramos, ao contrário, preserva em suas imagens um distanciamento que é analítico e que reforça, a uma só vez, o caráter misterioso e desconhecido de seus materiais.

Ainda que haja a mediação de imagens fotográficas na construção de parte significativa das pinturas de Patricia Leite, a artista imprime a força de uma pulsão escópica em seus resultados. A imagem técnica não parece interessá-la como algo a ser transferido ou traduzido em linguagem pictórica, mas, sim, pelo que a define como aparato: ou seja, por enquadrar o mundo, por estabelecer ângulos de observação próprios, por congelar o tempo, por controlar luminosidade, pelas distâncias focais que alcança, por dar a ver aquilo que nem sempre os olhos são capazes de enxergar, ou pelo menos não da mesma forma que a imagem técnica consegue. Assim, a artista transfigura a paisagem para uma condição ao mesmo tempo elementar e alterada.

A partir da suposta objetividade da fotografia, Patricia Leite simplifica as formas de seu campo de visão. Quase daria para dizer que Patricia pinta o contorno, a silhueta de seus objetos, convertendo-os ao plano bidimensional, modificando, intensificando ou suavizando cores e luzes por meio de um labor manual minucioso – e que, cada vez mais, tem deixado suas pinceladas aparentes –, mas que não almeja a perfeição. Com isso, por exemplo, o contorno das figuras deixa escapar as camadas de cor que vêm por trás, as etapas anteriores do processo da pintura, e que fazem aquela imagem acender-se ou vibrar. E, de fato, isso confere, ao mesmo tempo, certa artificialidade e um tanto de vivacidade a seus motivos, que são quase sempre “naturais”.

Também as imagens produzidas por Leticia Ramos tendem a certa imprecisão. Não costuma ser simples adivinhar o que cada trabalho mostra, que lugar é aquele, que situação é aquela, onde e como aquilo foi produzido, com que aparato, com que técnica e quando (a que tempo, afinal, pertencem essas imagens?). Diante de uma obra da artista, é de interrogar-se mesmo sobre a veracidade do que se vê: se aquilo é real ou imaginário, se é um flagrante ou o registro de uma situação montada, falsa, fantasiosa. Supõe-se que haja alta tecnologia mobilizada nessa produção, já que os trabalhos, não raro, aparentam ser itens de laboratório, de observação científica, destinados ao estudo, mas sem a assepsia desses ambientes. Até pela raridade dos acontecimentos que exibem, os trabalhos parecem constituir testemunhos.

Por tudo isso, é que a produção da artista se situa entre a ficção e o documento. As obras de Leticia Ramos reportam aos primórdios do cinema e às primeiras fotografias de corpos e fenômenos celestes, ao mesmo tempo em que testam os parâmetros contemporâneos das linguagens fílmicas e se valem do conhecimento recente acerca do universo. Outro paradoxo é que, embora dê a impressão do uso exclusivo de tecnologia de ponta, a feitura dos trabalhos é bastante manual – não só pela construção de máquinas, cenários e maquetes, mas também por operações mecânicas como riscar, recortar e colar negativos fotográficos. Pela própria materialidade do trabalho, instaura-se uma atmosfera de aparição, de algo espectral e fantasmático, nessas imagens; que são, em última instância, impressões luminosas de situações longínquas (por mais próximas que estejam) e aparentemente prestes a desaparecer.

O nome da exposição ressoa o título de um dos principais livros de poesia de Haroldo de Campos: Galáxias. Nessa obra, escrita ao longo de 13 anos, de 1963 a 1976, o poeta, escritor e ensaísta apresenta 50 cantos, ou fragmentos textuais, em uma escrita corrida e direta: sem pontuação, parágrafo, numeração de páginas, ou distinção entre prosa e poesia, gerando imagens e musicalidades caleidoscópicas. Com essa força que se propaga em todas as direções, Campos conecta idiomas, mistura palavras e lança mão de uma série de recursos literários — trocadilhos, duplos sentidos, repetições fonéticas e visuais, aliterações, assonâncias etc. —, abrindo uma dimensão irrestrita e incomensurável no universo da linguagem. A ideia — que o próprio título sugere — de que se formam ali constelações verbais não é à toa. E tem algo dessa vastidão, dessas articulações que ligam linguagens e elementos variados em gravitação, para o qual a exposição de Leticia Ramos e Patricia Leite também aponta desde o início.

Já na entrada da galeria vê-se a conjunção dos trabalhos: sobre a imagem de uma lua cheia, pintada em superfície de madeira (por Patricia Leite), projeta-se um vídeo (de Leticia Ramos) que simula um eclipse. Uma operação simples que, no entanto, materializa o fenômeno, ao atribuir extensão física e substância ao fenômeno e ao satélite. Na prática, a lua torna-se um campo de projeção e emissão de luz, que recebe e propaga brilho: com uma luminosidade que se forma, primeiro, na pintura, a partir do entorno daquele disco — por meio de demãos e tramas de tinta em cores diferentes, que acabam por conferir profundidade e intensidade àquele céu — e, depois, pelo feixe luminoso que incide e se reflete na superfície da lua, até seu encobrimento por outra imagem, a de uma sombra. A representação do eclipse lunar torna-se, assim, virtualmente pulsante, dinâmica, quase psicodélica — em parte, inclusive, por essa aproximação entre pintura, cinema e teatro que a proposta estabelece.

A exposição se organiza, daí em diante, como uma espécie de ensaio sobre a construção de paisagens, principalmente noturnas, a partir da observação do céu. Talvez seja, também, um ensaio sobre a capacidade que determinados equipamentos e técnicas têm de dar a ver fenômenos que os olhos, somente, não captam; ou sobre a possibilidade de refigurar esse ambiente intergaláctico — entre astros, corpos e acontecimentos celestes que são referentes espaciais e temporais, que dizem respeito ao passado, ao estado do mundo hoje, e ao que está por vir —como, por exemplo, a ameaça da queda do céu, em decorrência da destruição ambiental, segundo algumas cosmologias indígenas. Nesse sentido, talvez a mostra seja um ensaio sobre a intangibilidade, sobre aquilo que está distante no espaço, distante no tempo, e longe ainda da compreensão. O céu não é o limite, de uma vez por todas. Mas é um ponto de partida.

— José Augusto Ribeiro

-

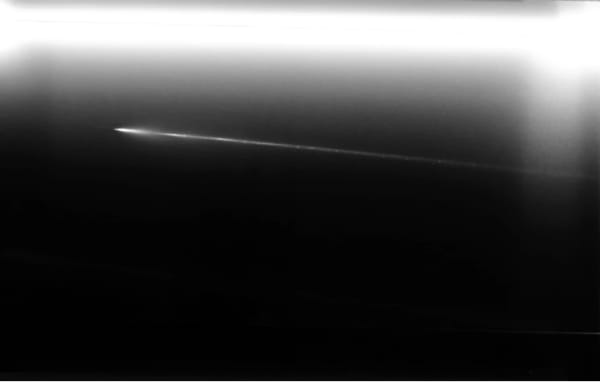

Leticia Ramos, Raio, 2024

Leticia Ramos, Raio, 2024 -

Patricia Leite, Ending, 2024

Patricia Leite, Ending, 2024 -

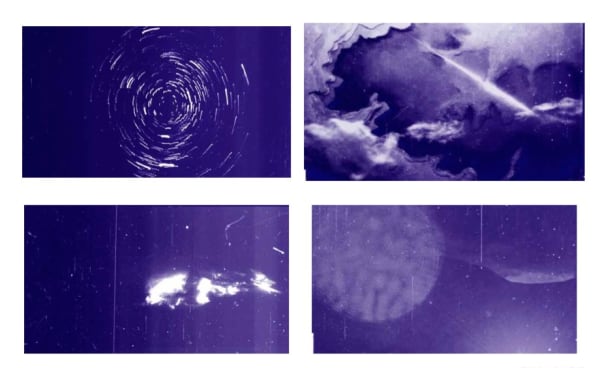

Leticia Ramos, Magnetic Field, 2018

Leticia Ramos, Magnetic Field, 2018 -

Patricia Leite, Lampejo, 2024

Patricia Leite, Lampejo, 2024 -

Leticia Ramos, Risco Final, 2024

Leticia Ramos, Risco Final, 2024 -

Patricia Leite, No céu de Magritte, 2024

Patricia Leite, No céu de Magritte, 2024 -

Patricia Leite, Estilhaços II, 2024

Patricia Leite, Estilhaços II, 2024 -

Leticia Ramos, Nuvem eclipse, 2024

Leticia Ramos, Nuvem eclipse, 2024 -

Leticia Ramos, Planisferio, 2017

Leticia Ramos, Planisferio, 2017 -

Patricia Leite, Estilhaços, 2024

Patricia Leite, Estilhaços, 2024 -

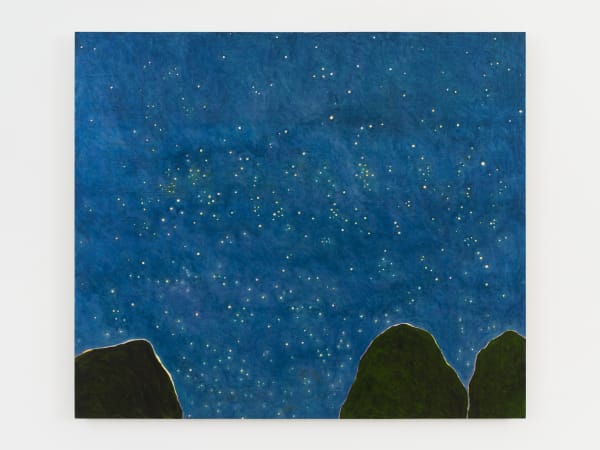

Patricia Leite, Constelado, 2024

Patricia Leite, Constelado, 2024 -

Patricia Leite, Estilhaços I, 2024

Patricia Leite, Estilhaços I, 2024 -

Patricia Leite, Início, 2024

Patricia Leite, Início, 2024 -

Leticia Ramos, Black Panorama II, 2018

Leticia Ramos, Black Panorama II, 2018 -

Leticia Ramos, The Blue Night, 2017

Leticia Ramos, The Blue Night, 2017 -

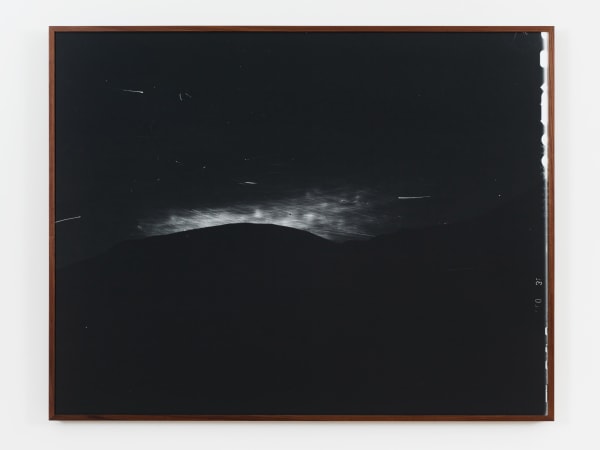

Leticia Ramos, Montanha, 2024

Leticia Ramos, Montanha, 2024 -

Leticia Ramos, Eclipse 01, 2024

Leticia Ramos, Eclipse 01, 2024 -

Patricia Leite, Perigeu, 2024

Patricia Leite, Perigeu, 2024 -

Patricia Leite, Galáxias, 2024

Patricia Leite, Galáxias, 2024 -

Patricia Leite, Boreal, 2024

Patricia Leite, Boreal, 2024