Um galo sozinho não tece uma manhã Guglielmo Castelli

Guglielmo Castelli: Painting as Revolution

A well-known fact is that Guglielmo Castelli is a painter from Turin whose craft was perfected during his academic training in scenography. This discipline has shaped his painterly practice in many ways, especially his rendition of space and architectural interiors. While his aesthetic is rooted there, a keen interest in literature and poetry combined with a critical perspective of bourgeois culture, which he grew up in, mark his intellectual horizon. The painterly surface, in fact, is not an expression of his technical virtuosity. It’s the battleground upon which Castelli makes sense of the culture surrounding him: the weight of heritage, high culture’s relationship to conservativism versus the popular, the bearings of it all on his imagination, and the possibility of total upheaval.

“Within painting, everything! Outside of painting, nothing!” Castelli and I joked as I was visiting his studio in Turin, playing on Fidel Castro’s famous “Within the Revolution, everything! Outside of the Revolution, nothing!” During my visit, while we spoke about painting, technique, abstraction, and form, the conversation never strayed much from current events. In Italy, a debate was resurfacing about the aesthetics of Fascism prompted, in part, by the release of a television series based on Antonio Scurati’s award-winning novel, M Son of the Century, about Benito Mussolini’s ascent to power. Meanwhile, under a right administration in the country, an educational reform set out to return the Bible to every classroom. In parallel, war as ever dominated the headlines from Congo to Palestine, Trump was sworn into the White House. All these things I could see play out on the surface of Castelli’s works that, in his words, reflect on “the exercise of and subjection to power.”

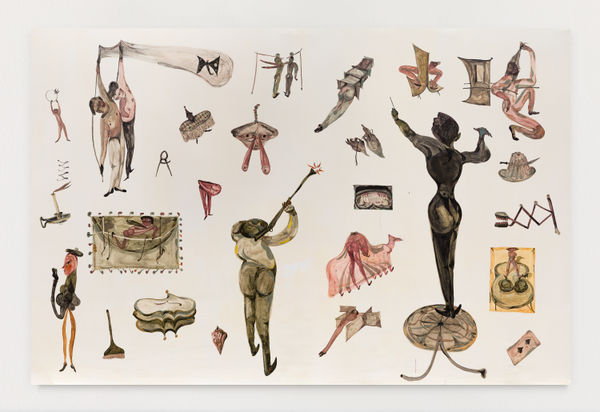

However, the paintings we see do not relay explicit political messages, nor do they offer a narrative representation of them. Instead, contortionist and fragmented bodies, limbs, masks, flora, and fauna, are beautifully painted in layers of oil onto paper, canvas, and found objects like tambourines. The paint is skilfully layered rendering flesh, transparencies, darkness, and light, generating seductive, quasi-gothic atmospheres where horror has a role in processes of recovery, renegotiation, reimagination – think of the atmospheres conjured in gothic novels like Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, Bram Stoker’s Dracula or Oscar Wilde’s Picture of Dorian Gray, texts known to capture a need to reconnect with the visceral in times of deep conservativism. Horror, in literature and paining, is a visual metaphorical regime through which the political and the social may be explored.

For many viewers, Castelli’s brand of figuration has engendered a reading of his work as oneiric and indebted to Surrealism. Without a doubt, Castelli is deeply informed by his studies of the Western canon of art, and above all of twentieth-century European avant-gardes including Surrealism – endemic to that bourgeois upbringing that he self-deprecatingly mocks and systematically seeks to question and reform. Yet, in my view, this interpretation is misguided when one considers the very premises behind Castelli’s conceptual frameworks, and his overall process, which departs from abstraction and considerations around the relationship of form to substance – among the artist’s references Hermann Broch’s collection of poems from 1913-1949 titled Truth Only in Form (La verità solo nella forma. Poesie 1913-1949, Milan: De Piante, 2021).

Castelli’s forms, colors, and compositions are a direct consequence of their substance. Vice versa, the formal rigor of his works is endemic to their content. A concern for the balance between form and substance, or form and subject, has been fundamental to the work of artists working with geometric abstraction across the twentieth century. While abstractionists like Cubists sought the abstraction of form to achieve a new aesthetic vocabulary, others like Concretists sought in the purity of form itself the opportunity to express the inherent, everything that is not confined by the figure. In many ways drawing from and merging diverse abstract tendencies, Castelli makes his paintings first by dripping paint onto raw canvas, applying it without a preconceived idea of what the final work is going to look like. Upon appraising the hollows, gradients, and shades that appear onto the surface, Castelli then traces or discovers geometries of space, figures and forms – a sort of pareidolia (to see shapes or patterns in abstract forms, like clouds or anything), which he materially described as “liquefaction and emergence.” Crucial in the development of figurative elements is an expansive drawing practice, which fills notebooks together with notes and citations, that function as preparatory study for the paintings and large-scale works on paper.

The artist chose to title this first exhibition at Mendes Wood DM’s São Paulo gallery with Brazilian poet João Cabral de Melo Neto’s poetic verse: Um galo sozinho não tece uma manhã [One rooster alone does not tell a morning]. The poem is an ode to the multitude, to solidarity and collaboration. It first appeared in the collection A educação pela pedra [Education by Stone]. This collection was published in 1966 when Brazil was being governed by a military dictatorship that was to crack down on artists and intellectuals with increasing violence over the subsequent years. The metaphor of the rooster only being able to call forth the morning’s brightness, if accompanied by multiple others, resonates as much then as it does today. In addition, it seems no coincidence that Cabral Neto’s poem seems to reproduce the core concept of Gestalt psychology – the theoretical cornerstone of many artists working with geometric abstraction in Brazil in the 1950s and 1960s: the “whole” (of a system, an object, or an experience) is more than the sum of its parts; in other words, the effect of multiple elements together is greater than the sum of each individual part alone.

Upon this core principle, many of the Brazilian avant-garde (Concretists and Neoconcretists) built their practices, often premised on the spatialization of form, which Castelli too approaches for the first time in this exhibition. While absolutely at one with his long-standing research and practice, Castelli has expanded the perimeters of his research by breaking through the fourth dimension and creating an immersive installation, or a set for his works to be shown in. His architectural intervention alters the viewer’s perception of the gallery while being led to walk over a raised platform that leads to three large-scale works. There is a sense of vertigo in being raised above ground, which is the same sensation evoked in the works where Castelli uses kaleidoscopic perspectives to offer an alternative viewpoint. The drawings that cover the floor below the platforms also make the onlooker aware of their corporeality in relation to the work.

At least three works Castelli made in response to his first visit to Brazil and for this exhibition are distinguishable by a warm palette in the tones of orange, red, and yellow. The canvas Pan de Queijo (2024), is a self-portrait of sorts representing a form of disorientation. The central figure finds itself in a cityscape; the architecture is indistinguishably European or colonial, though its perspective is skewered and twisted. It is as though Castelli’s systematic questioning of his own heritage resurfaces in a different key when having to confront the question of coloniality in a country like Brazil (interesting is also the misspelling deliberately kept in the title “pan de queijo” instead of “pão de queijo”). The canvas seems to ask, how does a gaze shaped by European canons and conventions transform in the face of a postcolonial context? How can a European artist make work that addresses and reforms European culture in Brazil? How can difference of perspective be accounted for?

The canvas Moleque (2024) pays homage to Italian-Brazilian artist Alfredo Volpi who emigrated as a child from Lucca to São Paulo in 1898. Celebrated as a pioneer of Brazilian modernism in his lifetime and today, Volpi imagined a modernism in Brazil untethered to a European one. He found his visual lexicon in a Brazil of the people, most notably through the iconic painting of the little decorative flags (Bandeirinhas), used in rural festivals and metonymic of popular Brazilian culture at large. Volpi’s Bandeirinhas occupy the foreground and often fill the canvas – symbolically the popular is at the forefront of the modern in Brazil. In contrast, Castelli scatters them around two main figures, who could be the titular slang word moleque – the kid(s) playing on the street. Next to them, two dogs fighting and a rooster appear consolidating that sense of a rural scene, a similar one to those Volpi would have sought to capture. Yet in Castelli’s work, the popular imagery is expressed in tension with an aesthetic that remains informed by Castelli’s formal training and knowledge of European art. In this work, the Bandeirinhas become a reproducible device, much like a grid – canonical modernism’s ubiquitous device, which we see rest in the background of another work Oh after, after (2024). So Castelli deploys the Bandeirinha as the tell-all of modernism – but this time of a modernism geared toward the popular.

Thinking around the popular emerges also in Castelli’s choice to exhibit found antique leather tambourines onto which he painted miniature scenes. Tambourines are instruments widely used in popular song internationally, in Italy essential to the canzone napoletana, a quintessential expression of popular song in Naples. Meia-dia (2024), shows a rural scene of lush vegetation and rolling hills in Castelli’s Brazilian palette with three figures holding butterfly nets. The activity of butterfly hunting seems incongruous with the heat conveyed by the palette and confirmed by its title (once again a misspelled meio-dia, midday), with the casual attire of the three, and generally at odds with frequent depictions of this leisurely and mundane activity conducted by men and women at the turn of the twentieth century. The second tambourine, Meia-noite (2024), returns to the darker palette familiar to Castelli’s broader oeuvre. This work presents a single disjointed figure lying over a staircase with ghostlike projections surrounding it. The dialogue between Meia-noite(midnight) and Meia-dia underpins some of the incongruences or fractures that Castelli is exploring within his own heritage, in a permanent search around the relationship of substance to form.

Such preliminary visual and contextual analyses express how Castelli’s panting is the end product of an ongoing research process prompted by a relentless questioning and renegotiation of cultural paradigms, from the Western canon of art to visions of the popular. Drawing from poetry, children’s rhymes, all narrative genres, to political events and the history of art, Castelli searches for ways to adapt and to “attempt a recalculation” (his words) of what hegemonic structures hand down to us as culture. For Castelli, painting really is the Revolution.

– Sofia Gotti

-

Guglielmo Castelli, Imitação da forma, 2024

Guglielmo Castelli, Imitação da forma, 2024 -

Guglielmo Castelli, Meia-dia, 2024

Guglielmo Castelli, Meia-dia, 2024 -

Guglielmo Castelli, Meia-noite, 2024

Guglielmo Castelli, Meia-noite, 2024 -

Guglielmo Castelli, Moleque, 2024

Guglielmo Castelli, Moleque, 2024 -

Guglielmo Castelli, pan de queijo, 2024

Guglielmo Castelli, pan de queijo, 2024 -

Guglielmo Castelli, Strong curls, happy years, 2024

Guglielmo Castelli, Strong curls, happy years, 2024 -

Guglielmo Castelli, 37 years, 2024

Guglielmo Castelli, 37 years, 2024 -

Guglielmo Castelli, Broken heart melody, 2024

Guglielmo Castelli, Broken heart melody, 2024 -

Guglielmo Castelli, Fofoca, 2024

Guglielmo Castelli, Fofoca, 2024 -

Guglielmo Castelli, The nearness of harm, 2024

Guglielmo Castelli, The nearness of harm, 2024 -

Guglielmo Castelli, Oh after, after, 2024

Guglielmo Castelli, Oh after, after, 2024 -

Guglielmo Castelli, With clues, one finds direction; with Evidence one convicts, 2024

Guglielmo Castelli, With clues, one finds direction; with Evidence one convicts, 2024 -

Guglielmo Castelli, Glorious wrecks, 2024

Guglielmo Castelli, Glorious wrecks, 2024 -

Guglielmo Castelli, Pinova, 2024

Guglielmo Castelli, Pinova, 2024 -

Guglielmo Castelli, Um galo sozinho não tece uma manhã 2, 2025

Guglielmo Castelli, Um galo sozinho não tece uma manhã 2, 2025 -

Guglielmo Castelli, Um galo sozinho não tece uma manhã 4, 2025

Guglielmo Castelli, Um galo sozinho não tece uma manhã 4, 2025 -

Guglielmo Castelli, Um galo sozinho não tece uma manhã 3, 2025

Guglielmo Castelli, Um galo sozinho não tece uma manhã 3, 2025 -

Guglielmo Castelli, Um galo sozinho não tece uma manhã 1, 2025

Guglielmo Castelli, Um galo sozinho não tece uma manhã 1, 2025