À bença meus padrinhos Wallace Pato

Pato is a self-taught artist who began his practice around six years ago. His works connect the landscape of North-East Brazil to the imagery of Rio de Janeiro, performing a sort of chronicling exercise by painting street walls. His vernacular paintings tell stories that illustrate aspects of Brazilian culture. His narrations fuse images of popular parties, children on the streets, carnival scenes, meals and funerals. Pato shows great respect for the detail, composing images derived from familiar stories: “I paint working-class suburbs, I paint Brazil. I have several objectives, but I think the greatest one is to be a spokesperson for those who have never been heard. People who are giants, and have a lot of strength, who carry an immense history, who carry a lot on their backs, but who never had the chance to speak up, or when they did, their voices were blocked out”.

The current exhibition is directly linked to the history of samba. It illustrates moments of the creation of this artistic movement that has elevated Brazilian culture to its ultimate expression. Samba originates from rhythms brought to Brazil by enslaved Blacks, and by the end of the Empire and the beginning of the New Republic, it began to gradually spread across Brazil, occupying a space of resistance and celebration, almost always furtively, in response to the slave-owners’ inclement refusal to accept the humanization of Black people. In grandparents’ houses, meetings at terreiros and other places of worship, suburban streets, alleys or lanes, this musical culture eventually landed at samba circles in bars, establishing a pillar of freedom against conservative forces and the rigid concepts that insisted on limiting the creative potential of an entire people.

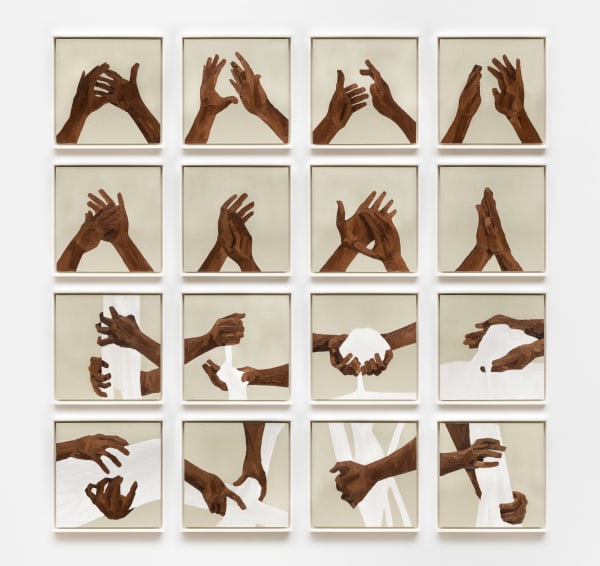

Dona Ivone Lara, known as the Great Dame of Samba, was the first woman to join the composers’ section in a samba school, as well as the first woman to play the cavaco (string instrument). Here, she is portrayed at the center of Pato’s painting, surrounded by men. In Pato’s narrative, Lara’s power outlines the artist’s desire to highlight not only some of the cultural elements of the samba scene but also its disruptive character, where female power takes centerstage. Buscar Dendê [To Search for Dendê] is a reference to capoeira – an Afro-Brazilian cultural expression whose practice was banned for many years. It borrows its title from a famous song by Mestre Maxuel often played in capoeira circles and depicts two boys performing its moves. Capoeira, and its accompanying practice of clapping hands, is recognizably one of the driving forces behind the rhythm that came to define the cadence of samba.

The work of Pato follows the origins of samba to find, in the field of visual arts, an artist who was one of the greatest names to depict the rite of carioca samba in his paintings. Heitor dos Prazeres (1898-1966) – one of the icons of Brazilian popular art who, as well as a painter, was a composer and a singer, and contributed to the creation of samba schools in Rio de Janeiro – appears surrounded by priestesses[AF1] , as a reference to his practice, bringing to life the pictorial context that characterized his oeuvre.

Cartola, Pixinguinha, Clementina de Jesus, Clara Nunes, amongst other icons, populate Pato’s exhibition, alongside characters connected to the artist’s family. Common people and faces, as well as memories from his upbringing, tell a story and build the pillars with which he introduces his references to the public. Whilst his artistic gestures are generous, Pato also hides in these images – which are sometimes understood to be summaries – the secrets behind these stories, encouraging the observer to study an untold plot. Wallace Pato both delivers and safeguards the place where he comes from, the floor on which he walks, reaching an almost rhythmic movement that simultaneously protects and shares what he finds sacred.